Volume 1, Issue 4, September–October 2020.

A Century of the Da Nang Museum

of Cham Sculpture

by Vo Van Thang

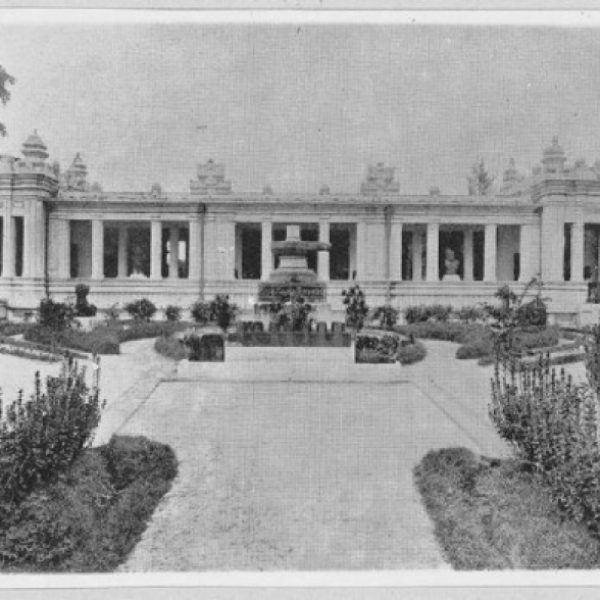

Đà Nẵng is a port city in Central Vietnam. Historical documents and ancient relics that have been found in the vicinity of Đà Nẵng show that the area was occupied by the people of the ancient kingdom of Champa from the early centuries of the first millennium to the fourteenth century CE.1 In the French colonial era, before World War II, the city was known in French as TouraneSome of the buildings from French colonial times can still be seen today in Đà Nẵng, the most special of them being the Musée Cham (Cham Museum), which was built in 1915 in the jardin de la ville de Tourane, on the scenic bank of the Hàn river. The 100 years of this museum’s existence have been intertwined with the historic changes that have taken place in Vietnam’s history. When the French ‘protectorate’ ended in 1945, the French-sponsored institutes were transferred to the new governments of Vietnam. Since 1963, in the turmoil of the complex war, the Musée Cham was put in the custody of the Saigon Archaeology Institute of the South Vietnam Government. When the war ended in 1975 with the collapse of the Southern Vietnam Government, the Musée Cham was affiliated as a department of the Provincial General Museum of Quảng Nam-Đà Nẵng. In 2007, it was re-established as an independent museum, with the official name of the Đà Nẵng Museum of Cham Sculpture (DMCS). The history of the museum can be reviewed as a mosaic of collection, conservation and exhibition of Cham artefacts for the public through the efforts of generations of enthusiasts for more than 100 years.

A century of collecting Cham objects

The ruins of the Cham temples caught the attention of the French scholars and antique collectors who were in various ways involved in the ‘protectorate mission’ in the provinces of central Vietnam from the end of the nineteenth century (Baptiste 2005; Brown 2013). As the Ecole Francaise d’Extreme Orient (EFEO) was established at the beginning of the twentieth century, the collecting and studying of Cham art was carried out with a more academic orientation. In 1901, Louis Finot, the first director of EFEO, published a research paper attached to an inventory in which he noted 68 objects from Cham sites that had already been collected at the Jardin de Tourane (Finot 1901, 32).

In 1902, Henri Parmentier, the head of the Archaeology Department of the EFEO, developed the idea of the “storage of Cham sculpture in Tourane”, and in the years that followed, as the collection grew with new finds, he proposed a purpose-built museum in Đà Nẵng, at the Jardin de TouraneParmentier said one of the reasons for the choice was that the Đà Nẵng region had been the centre of the Champa kingdom. Much debate then occurred among the governmental offices and the professionals before the final decision was made to start the construction of the museum in 1915. The museum was opened to the public in 1919 with the display of 268 objects.2 “The result was finally achieved, but it required seventeen years of patient effort.”3

After its inauguration in 1919, more objects were added to the museum’s collection as the results of archeological excavations. In 1927 and 1928, when Léonard Aurousseau was the director of EFEO, an investigation project was carried out at Trà Kiệu under the supervision of J.Y. Claeys. Some decades earlier, several impressive objects had been found in the area, including a big pedestal with elaborate carvings (Trà Kiệu pedestal BTC 95-22.2) and some artistic reliefs of dancing apsara (BTC 118/1-22.5). Scholars began thinking that Trà Kiệu must have been a capital of Champa, as mentioned in Chinese sources (Arousseau 1923). And the Claeys excavation in 1927-1928 was intended to clarify this hypothesis with a focus on architecture and sculpture (Glover 1997). The objects discovered raised the question of the date of the Cham settlement of Trà Kiệu. A relief of a Yaksa (BTC 136-22.2) suggested a date before the seventh century and a circular piece with a distinctive human breast motif indicated that it remained into the later centuries.

Another important excavation in 1934 at Thap Mẫm, Bình Định province, yielded an exceptional collection of remarkable objects. According to a report by J. Y. Claeys, 58 tons of stone objects were shipped to Đà Nẵng from the excavation siteThe objects were later transferred to the museums in Hanoi, Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City) and Huế (Claeys 1934). The major part was left in the Cham Museum of Đà Nẵng, and formed an impressive collection with a distinctive character. The Thap Mẫm monument, was judged from its structure and contents to belong to the thirteenth century, shortly after the end of Khmer occupation in central Champa. With the Thap Mẫm collection, the Cham Museum was in possession of a fully representative collection of objects typical of the key periods in the evolution of Cham art.

From 1945 to 1975, the archaeological missions were interrupted by the terrible and prolonged war in Vietnam. Despite the huge US airbase beside the city, just one single case is recorded of an American soldier transporting a Cham statue to the Museum in 1969 (Dvarapala BTC 279-9.15).

It is not clear from the records whether artefacts were damaged, stolen or moved. The current events (Chronique) section in several issues of the French EFEO Bulletin show boxes of objects being added to or transferred from the Cham Museum after 1919, but because the Museum archives and inventories vanished during the war it is difficult today to check what happened to the collection during these 30 dark years.

The fortunes of the Cham Museum changed dramatically in the post-war reconstruction period in all localities in the provinceIn the 1980s, 20 objects were discovered at the Cham ruin at Qua Giang while the site was being cleared. In 1982 the excavation of an irrigation channel in An Mỹ uncovered a Cham temple foundation. The Museum was called in and the investigation collected three busts, five broken statues and other fragments in sandstone. Their style was so distinctive that the artefacts were designated as being in the “An Mỹ style” (Phương 1983). In the Khue Trung suburb of Đà Nẵng city, villagers restoring their local temple discovered two yoni covered by the roots of a banyan tree and alerted the Museum. Of particular importance was a sandstone pillar with inscriptions on each of its four faces that was unearthed by a Khue Trung family while digging the foundations of their new houseThe inscription in Sanskrit and the Old Cham language is dated in 899 CE and discloses the existence of a monastery in the area (Griffiths 2012: 263-270).

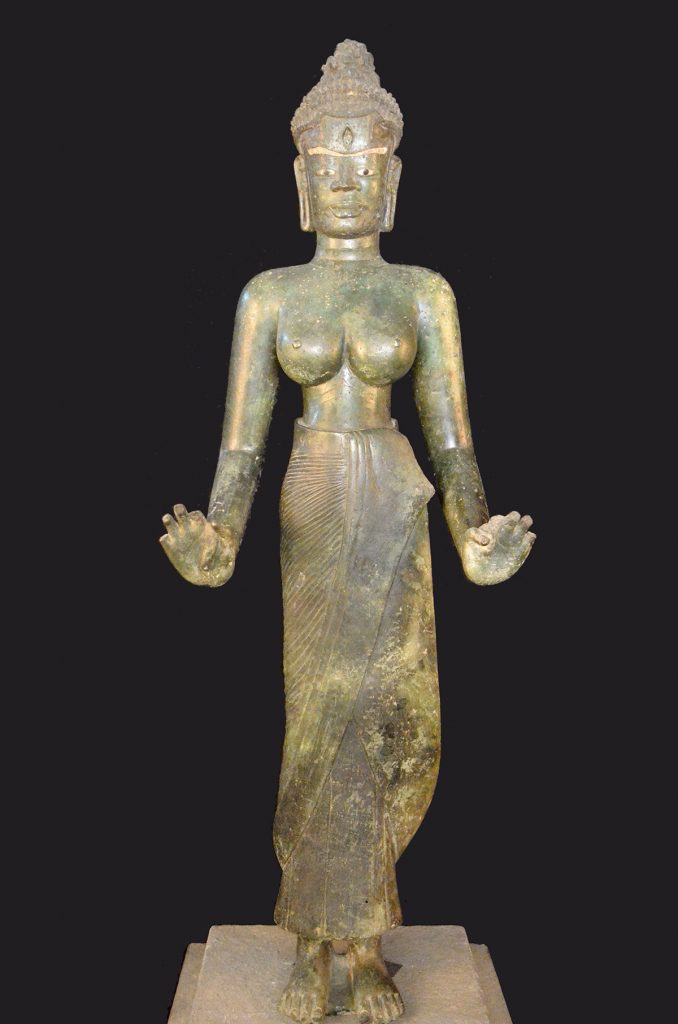

The most memorable recent discovery came in 1979 when a farmer uncovered a Cham bronze masterpiece amid the thousands of tons of collapsed brick sanctuaries in the ruins of the great ninth century Đồng Dương Buddhist monument. The large, powerful and elegant bronze goddess was subsequently designated a National Treasure of Vietnam. The bronze (BTC 1651), is thought to be the statue of the deity Laskmindra-Lokesvara, who is mentioned in an inscription found close to the location of the find. The goddess is the largest Cham bronze and is regarded as a masterpiece of Cham art. French scholar Jean Boisselier wrote: “It is no exaggeration to consider the discovery of this statue… as the most important event in the history of Cham art since the excavation of Thap Mẫm sanctuary in 1934.” (Boisselier 1984: 336)

In recent years, the DMCS carried out excavation projects in the suburbs of Đà Nẵng City. After French archaeologists announced the discovery of the dépôt sacré at Ponagar – Nha Trang (Parmentier 1909) and Đại Hữu – Quảng Bình (Arrouseau 1926), the excavation at Phong Lệ and Cấm Mít in Đà Nẵng in 2011–2012 provided a full view of the structure of the “underground space” in the centre of the Champa temple, where the consecration deposit had been placed. This was the first occasion the DMCS collection was extended with religious objects of gold and quartz from the sacred deposit of a Cham temple foundation (Thắng 2013).

Studying and cataloguing the museum collection

In the early decades of the twentieth century, along with his campaign for the construction of the museum, Henri Parmentier carried out the investigation of the Cham remains across the whole of Central Vietnam. Beside the reports printed on BEFEO, Henri Parmentier completed an important work with 598 pages and 134 figures entitled Inventaire descriptif des monuments Cam de l’Annam, volume I, which was published in 1909; the 571 pages and 173 figures of Volume II were published in 1918. In this great inventory work, Parmentier provided the basic information on the archaeological excavations and the first description of Cham objects with photos and drawings. These close examinations and field experiences helped Henri Parmentier compose the catalogue of the Cham Museum published in BEFEO in the same year in which the museum was opened to the public (1919). In this first catalogue we can find basic information on the provenance, description and documentation of the 268 objects displayed in the museum. With regard to the styles and dates of Cham sculptures, Parmentier proposed two major periods: 1. Primary periods (before 1000 CE), including “l’art primitif ” and “l’art cubique” that existed in parallel from the eighth to the tenth century; 2. Secondary periods (after 1000 CE), including ‘l’art classique” (11th century) and ‘l’art dérivé” (twelfth century and later). Parmentier put forward 45 categories and enumerated each object with category number and order number. The codes assigned by Parmentier are preserved as classification numbers on the Inventory of DMCS today.

In 1963, the EFEO published La Statuaire du Champa, recherches sur les cultes et l’iconographie by Jean Boisselier, an art historian specialised in Khmer and Cham art. This is a comprehensive monograph analysing the iconography and historical background of the hundreds of statues and reliefs at the Cham sites and at the museums in France and in Vietnam. The book included 257 photographs, 110 of which are photos of the objects at the Đà Nẵng Cham Museum and may be referred to as the first album of the museum collection. He inherited the terminology for Cham architecture styles initiated by Philippe Stern (1942) and classified Cham sculptures into eleven styles of evolution: 1. Early Hindu-influenced style (before seventh century); 2. Mỹ Sơn E1 style (627 – 757 C.E.); 3. Hòa Lai style (758 – 859 C.E.); 4. Đồng Dương style (875 – 915 C.E.); 5. First part of Mỹ Sơn A1 style (tenth century): the style of Khương Mỹ; 6. Second part of Mỹ Sơn A1 style: the style of Trà Kiệu; 7. Continuation of Mỹ Sơn A1 style: the style of Chanh Lộ; 8. Thap Mẫm style (end of the tenth century to 1177 C.E.); 9. Continuation of Thap Mẫm style (1220 – 1307 C.E.); 10. Yang Mum style (1307 – 1471 C.E.); 11. Po Rome style (after 1471 C.E). The judgements of Boisselier were very different from Parmentier on the group of objects from Trà Kiệu, many of which Parmentier had set in the seventh and eighth centuries and reassigned to the tenth century by Boisselier.4 In 1972, during the American war, the U.S. Information Service published The arts of Champa by Carl Heffley, the American advisor to Đà Nẵng City, with photographs and sketches by Nguyễn Xuan Đồng, Curator of the Cham Museum. This is a unique catalogue of 132 pages and 142 figures, published in wartime, which mentioned the January 1970 message of President Richard Nixon to the U.S. military commanders saying: ‘the White House desires that to the extent possible measures be taken to insure damage to monuments is not caused by military operation’.

After the war ended in 1975, the Cham Museum was managed by the Department of Culture and Information of Quảng Nam – Đà Nẵng province. The Department invited Mr Nguyễn Xuan Đồng, a retired curator, to be re-employed at the museum from 1977 to 1986. Under the direction of Mr. Đồng, an inventory document was compiled in the format of a catalogue. The document was hand-written by Mr. Ngô Khôn Lieu of the museum staff, and consisted of four notebooks, 21 x 28cm in sizeIt constitutes the earliest unprinted catalogue of the museum in the Vietnamese Language. It presented basic information on the 291 objects on display and did not record the many objects in storage and lying scattered in the museum garden.

In the immediate post-war decades financial and human resources were few and there was little research or investment in museological matters.

In 1987, a trilingual (English, Russian and Vietnamese) catalogue was printed by the Foreign Language Publishing House in Hanoi, entitled the Museum of Cham Sculpture in Đà Nẵng, edited by Trần Kỳ Phương, who was working at the museum. The catalogue provides photographs of 49 objects, some of them collected after 1975. In the introduction, Trần Kỳ Phương identified six styles in Cham art, two of them quite different from Boisselier in 1963, iethe early Trà Kiệu style in the seventh century and the An Mỹ style in the eighth century. Another trilingual (Vietnamese, English and Japanese) Cham Sculpture Album was published in 1988 by the Social Sciences Publishing House in Hà Nội with an Introduction by Phạm Huy Thông and photographs by Nguyễn Văn Kự and Phạm Ngọc Long. A research text by Cao Xuan Phổ identified 6 periods in Cham art: Mỹ Sơn E1 (first half of eighth century), Hòa Lai (first half of ninth century), Đồng Dương (end of tenth century), Trà Kiệu (end of ninth – beginning of 10th century), Thap Mẫm (twelfth-thirteenth centuries), and Po Klaung Garai (13th–16th centuries).

A comprehensive catalogue in French, Le Musée de Sculpture Cam de Đà Nẵng, appeared at the end of the twentieth century. The catalogue was realised under the direction of Léon Vandermeersch and Jean-Pierre Ducrest with support from the Association Francaise des Amis de l’Orient and EFEO. The English version was printed in 2001 entitled Cham Art – Treasures from the Đà Nẵng Museum, Vietnam. As Léon Vandermeersch acknowledged:

Jean Boisselier had been working on a project to publish descriptions and dates for the sculpture, including a classification of the photographs according to the artistic merit and iconography of each work of art (…). Boisselier had begun drafting the text when he fell ill, and foreseeing a fatal outcome, chose Emmanuel Guillon as his successor to complete the book.

In this catalogue, each object was noted with a style – inherited from Boisselier 1963, and a definite century date.

The twenty-first century opens new opportunities for the museum along with the full integration of Vietnam into global cooperation. The Đà Nẵng Museum of Cham Sculpture joined research and exhibition cooperative projects with the museums and institutes in France, Japan, the United States, India and the United Kingdom. In 2005, DMCS sent 47 objects to an exhibition at the museum of Guimet, Paris. The objects were introduced in the exhibition catalogue, “Trésors d’art du Vietnam: La sculpture du Champa, V – XV siècles”, edited by Pierre Baptiste and Thierry Zéphir. In 2009, nine objects from DMCS were displayed in Houston and New York and appeared in the catalogue “Arts of Ancient Vietnam: From River Plain to Open Sea”, edited by Nancy Tingley. Another exhibition in the United States with the presence of 5 objects from DMCS was held at the Metropolitan Museum, New York, in 2014. The catalogue was edited by John Guy and bore the title of the exhibition “Lost Kingdoms – Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia”. A book “Cham Sculpture and Indian Mythology” written by Huỳnh Thị Được, a staff member of the DMCS, was published in 2006, consisting of 76 pages and 127 figures. This is a shortened English version of the book Đieu khắc Chăm và Thần thoại Ấn Độ, printed in Vietnamese in 2005 with texts and photos of 75 objects from the museum, which aligns many sculptures closely with the Indian myths.

In 2012, the book “Văn khắc Chămpa tại Bảo tàng Đieu khắc Chăm Đà Nẵng” (The Inscriptions of Campā at the Museum of Cham Sculpture in Đà Nẵng) by Arlo Griffiths, Amandine Lepoutre, William A. Southworth & Thành Phần was published in collaboration between École française d’ExtremeOrient, Hà Nội and Center for Vietnamese and Southeast Asian Studies, Vietnam National University of Ho Chi Minh City. The book contains the first ever complete study of the inscriptions of Champa preserved at DMCS.

Changing the display – The first display in 1919

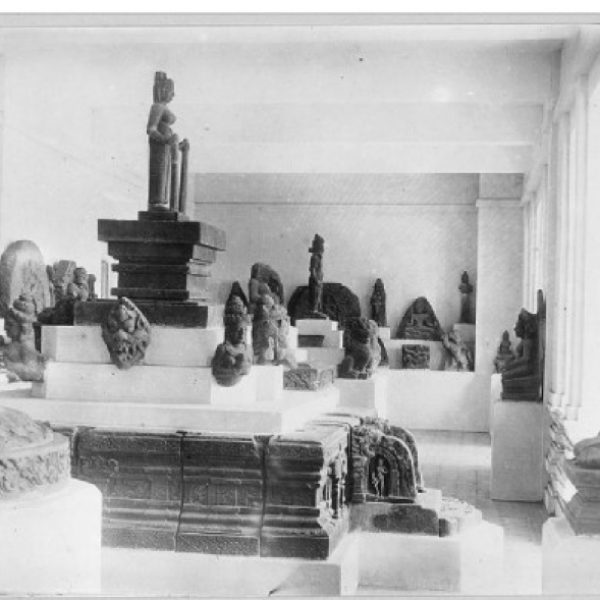

The first museum building was constructed in 1915 with a rectangular plan of 306 m2 , consisting of a central large space and four surrounding corridors with many open windows. The objects were displayed fixed on the walls or onto cement podiums both inside the building and outdoors. A total of 268 objects were displayed with 53 objects from Trà Kiệu, 30 objects from Mỹ Sơn and many others of uncertain provenance, which were noted temporarily as from “le jardin de Tourane” (Parmentier 1919).

The objects were arranged to create a strong impression on visitors without grouping them in terms of provenance or dateThe pedestal of Mỹ Sơn E1 (BTC 6-22.4) was sited in the central space beside a statue of a bodhisattva from Quảng Bình (BTC 188-14.3). In the front courtyard, a row of seven carved linga from Mỹ Sơn (2.4) was displayed next to the pedestal of Trà Kiệu (BTC 118/1-22.5) (Baptiste 2005).

The second display in 1936

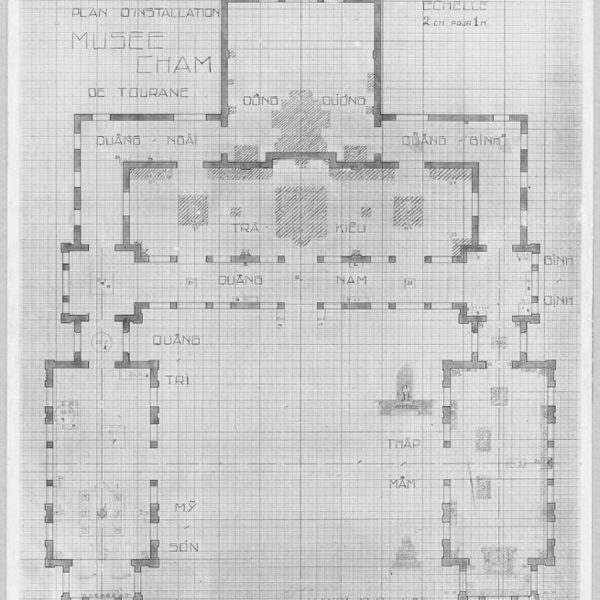

In 1935, the museum was expanded with the addition of two new lateral rooms (each measured at 130m2) Another room (approximately 100m2 ) was added at the back of the building. The total area for display now reached 710 m2 , which doubled the size of the original building.

The 1936 display made some remarkable changes to the galleries:

– Sculptures were grouped into galleries named after the excavation sites, including the galleries of Mỹ Sơn, Quảng Trị, Quảng Nam, Quảng Ngãi, Quảng Bình, Bình Định, Thap Mẫm, Trà Kiệu, Đồng Dương.

– Architectural components from the temples were incorporated into the displays. For example the wrestlers from Khương Mỹ (24.2) were fixed alongside the doorsteps of Quảng Nam gallery; temple pillars were set into the walls, making door frames for the galleries of Mỹ Sơn and Quảng Trị; temple foundation components were used for decorative lines below the windows in Thap Mẫm gallery; and mythical animals were displayed in pairs at the gate leading to the museum. All the galleries since 1936 were mostly preserved over the following 60 years and their detailed plans with every object can be seen in a drawing by Po Dharma in the catalogue Le Musée de Sculpture Cam de Đà Nẵng (1997).

The third display in 2002

After 1975, more sculptures entered the museum and a two-storey building was annexed to the back of the existing structure with the first floor offering 1500 m2 and the second a further 550 m2. In 2002, the museum developed a new display in this building on its first floor and entitled it “The New Collection”. Exhibits included those not selected for the 1936 display and those excavated after 1975. The second floor was used for temporary exhibitions while other galleries in the old building were preserved as in the 1936 plan.

Although more objects were thus exhibited to the public, the display challenged the visitors’ itinerary because there were overlaps in the theme and provenance of the objects in the old galleries and the others in the new rooms.

The FSP project and two model galleries in 2009

Since 2004, the Cham Museum has undergone another renovation under the FSP project (Fonds de Solidarité Prioritaire de Revalorisation du Patrimoine Muséographique Vietnamien), which aims at modernizing the museums in the post-colonial period.

Project specialists suggested an overall exhibition map connecting all the museum buildings. The arrangement of galleries followed the chronology of the sculptures, which meant several galleries had to be relocated. The circulation flow of visitors is now directed in an orderly way through the four main collections: Mỹ Sơn,5 Đồng Dương,6 Trà Kiệu,7 Thap Mẫm.8 Other collections are displayed in auxiliary areas.

As for the technique, FSP experts recommended that all sandstone objects be removed from the wall or from cement bases to stop the bad effects of humidity. They were to be reinstalled independently on plinths with frames made of iron, and backed by panels of rough grey sandstoneIn terms of lighting, new galleries employ the spotlights from the ceiling to illuminate the objects on view. Some windows are blocked to control the effects of light. The high ceilings make use of natural light and also keep the exhibition space ventilated.

Within the framework of this project, the galleries of Mỹ Sơn and Đồng Dương were selected for renovation and subsequently inaugurated in 2009. The other galleries remain unchanged for the moment due to budgetary constraints.

The renovation in 2016-2017

At the centenary celebration of the Cham Museum in 2015, a proposal was presented to the Đà Nẵng city authority for the restoration and refurbishment of the 100 year-old museum. The project was approved and started in 2016, aiming to refurbish worn sections of the buildings and provide some expansion of exhibition space for the museum’s second century. The expanded section adapted the architectural design of the old constructions of 1915 and 1935, which are the impressive legacy left by the pioneers and regarded as a unique aspect of the museum.

Besides the maintenance and improvement of the buildings, the display plan was adjusted to provide a more convenient itinerary through the structure for visitors. Following the principles sketched in the FSP project, all the objects on walls and cement podiums were redisplayed using the same technique applied on the Mỹ Sơn and Đồng Dương galleries in 2009. An itinerary for visitors was planned on a new object-oriented basis (Dean 1994: 4). Currently, the museum collections have clear provenance, yet still contested dating. Objects have therefore been arranged in galleries named after their excavation sites while still following a visible chronology. This display system enables visitors to track the stylistic evolution of Cham art and appreciate the rich variety of sculptural themes and styles from certain periods and localities. Visitors are encouraged to start in the Trà Kiệu gallery then move to the Mỹ Sơn, Đồng Dương and Thap Mẫm galleries.9 An option remains to follow a geographical north-south order, ie Quảng Bình, Quảng Trị, Thừa Thien- Huế;10 Đà Nẵng;11 Quảng Nam;12 Quảng Ngãi,13 Bình Định and Kon Tum.14

The 2016 renovation reserves much space for temporary/thematic exhibitions and public events to meet the learning and entertainment needs of the public. In the first phase of the refurbishment, thematic exhibitions provide visitors with information on the formation and continuation of Cham culture in the context of Southeast Asian culture in general and of Vietnam in particular with a display of Champa inscriptions on the first floor and the Sa Huỳnh – Champa pottery galleries and “Festivals and Handicrafts of today Cham Communities” on the second floor.

Located in the cradle of the ancient Cham civilisation, the Đà Nẵng Museum of Cham Sculpture conserves the precious remains of the ancient kingdom of Champa. The museum itself has experienced manifold difficulties in the ups and downs of the past 100 years and still holds in its heart the mysterious potency of its collected, sacred and aesthetic stones. We owe our warmest gratitude to the generations of curators and conservators who have made this possible.

(V.V.T.)

Note

1 Kosa in religion and art of Champa, Vietnam Social Sciences mN3.2001, pp.39-44

2 J. Boisselier, La statuaire du Champa, Recherches sur les Cultes et l’Iconographie, EFEO, Paris, 1963, p.413.

3 Dr. Tran Duc Anh Son, Vietnamese Antique Objects in the world: treasures of the Cham dynasties, CAND, 21.07.2011.

4 Jean-Francois Hubert, Art of Champa, Paris, 2005.

5 Kosa in religion and art of Champa, Vietnam Social Sciences mN3.2001, pp.39-44

6 J. Boisselier, La statuaire du Champa, Recherches sur les Cultes et l’Iconographie, EFEO, Paris, 1963, p.413.

7 Dr. Tran Duc Anh Son, Vietnamese Antique Objects in the world: treasures of the Cham dynasties, CAND, 21.07.2011.

8 Jean-Francois Hubert, Art of Champa, Paris, 2005.

9 Kosa in religion and art of Champa, Vietnam Social Sciences mN3.2001, pp.39-44

10 J. Boisselier, La statuaire du Champa, Recherches sur les Cultes et l’Iconographie, EFEO, Paris, 1963, p.413.

11 Dr. Tran Duc Anh Son, Vietnamese Antique Objects in the world: treasures of the Cham dynasties, CAND, 21.07.2011.

12 Jean-Francois Hubert, Art of Champa, Paris, 2005.

13 Kosa in religion and art of Champa, Vietnam Social Sciences mN3.2001, pp.39-44

14 J. Boisselier, La statuaire du Champa, Recherches sur les Cultes et l’Iconographie, EFEO, Paris, 1963, p.413.

References

Aurousseau 1926: Léonard Aurousseau , “Nouvelles fouilles de Đại-hữu”, BEFEO, XXVI, 1926, pp. 359-362.Baptiste 2005: Pierre Baptiste, “Le Musée de Đà Nẵng et le dévelopment des études cham: le temps des pionniers (1886-1936)”, in Baptist, Pierre & Thierry Zéphir (ed.), Trésors d’art du Vietnam: La sculpture du Champa, V – XV siècles, Guimet – Musée National des Arts Asiatiques, Paris, 2005, pp. 3-11.

Boisselier 1984: Jean Boisselier, “Un bronze de Tārā du Musee de Đà Nẵng et son importance pour l’histoire de l’art du Champa”, BEFEO, LXXIII, 1984, pp. 319-338. Brown 2013: Julian Richard Brown, The Field of Ancient Cham Art in France: a 20th century creation – A study of museological and colonial context from the late 19th century to the present (PhD diss., SOAS, University of London, 2013).

Claeys 1934: Jean-Yves Claeys, “Annam (rapport sur le fouille de Thap Mẫm)”. BEFEO, XXXIV, 1934, pp.755-759.

Dean 1994: David Dean, Museum Exhibition: Theory and Practice London: Routledge, 1994.

Finot 1901: Louis Finot, “La religion des Chams d’après les monuments, étude suivie d’un Inventaire sommaire des monuments Cham de l’Annam”, BEFEO I, 1901, pp. 12-32.

Glover 1997: Ian C. Glover, “The excavations of J.Y. Claeys at Trà Kiệu, Central Vietnam, 1927–1928: from the unpublished archives of the EFEO, Paris and the records in the possession of the Claeys family”, in Journal of the Siam Society, Vol 85, part I & II, 1997, p. 173-186.

Griffiths 2012: Arlo Griffiths, Amandine Lepoutre, William Southworth & Thành Phần, Văn khắc Chămpa tại Bảo tàng Chăm-Đà Nẵng/The inscriptions of Campà at the Museum of Cham Sculpture in Đà Nẵng, VNU-HCM Publishing House, HCM City, 2012. Parmentier 1909: Henri Parmentier, “Découverte d’un nouveau dépôt dans le temple de Pô Nagar de Nha-trang”, BEFEO, IX, 1909, pp. 347-351.

Parmentier 1919: Henri Parmentier, 1919, “Catalogue du musée Cam de Tourane”, BEFEO, XIX, 1919, pp.1-114.

Phương 1983: Trần Kỳ Phương, “A Newly Discovered Cham Site: An Mi (Quảng Nam – Đà Nẵng)”, Tạp chí Khảo cổ học (Magazine of Archaeology), No 3/1983, Institute of Archaeology, Hà Nội, pp. 33-37.

Stern 1942: Philippe Stern, L’art du Champa (ancien Annam) et son evolution, Toulouse, 1942.

Thắng 2013: Võ Văn Thắng, “Kho thieng trong lòng thap Chăm: Từ văn bản cổ Ấn Độ đến phat hiện khảo cổ” (The sacred deposit in Cham temple: from ancient Indian texts to archaeological findings), Tạp chí Khảo cổ học (Magazine of Archaeology), No 6/2013, Institute of Archaeology, Hà Nội, pp. 25-38.