Volume 2, Issue 3, May-June 2021.

New Directions in the Research

of Historical Networks of Khmer Settlements

by Dr. Károly Belényesy

Koh Ker, Cambodia

The inventory, processing, restoration and preservation of Khmer cultural heritage is the result of major international cooperation. The fact that millions of tourists visit the fascinating buildings of the Angkor region every year is an accolade for the systematic work of many local and foreign researchers and research teams, and it is a particular source of pleasure that Hungarians have been increasingly able to get involved and follow in the footsteps of French, Japanese, Australian, Chinese and Indian experts, and what’s more, have laid new milestones in the research of the tenth-century capital.

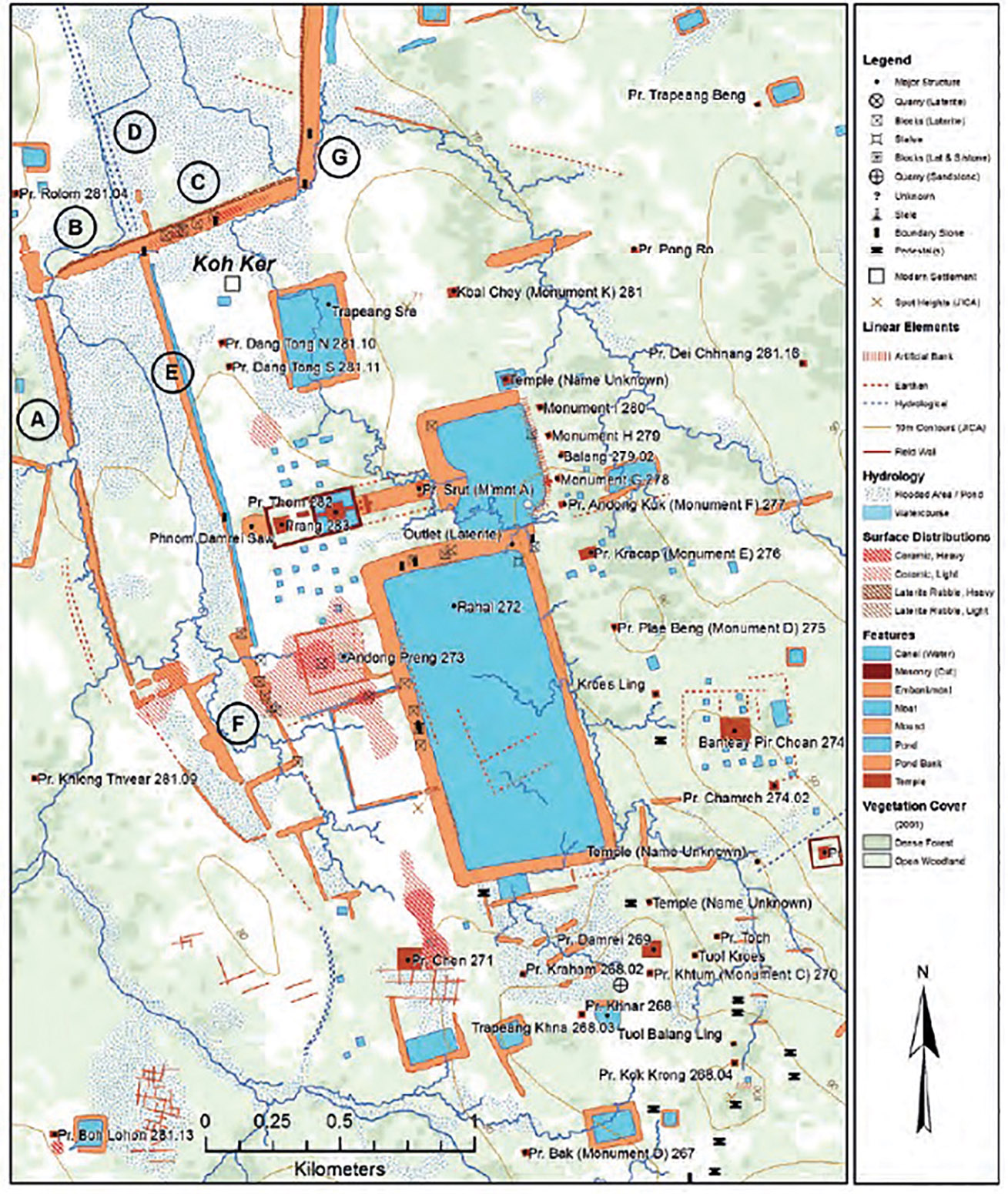

The location of our research is Koh Ker, situated about 100 km from the renowned Angkor, at the crossroads of the trade routes to the one-time north-northeast regional centres of Vat Phou (now Laos) and Preah Vihear (Cambodia). The 80km2 of protected forest and the area occupied by a series of 10th–13th century Khmer temples and small shrines got its current name from the eponymous village of Koh Ker, which is populated by just a few hundred souls. In connection with its history, however, it is widely believed that between 928 and 944 the ‘Chok Gargyar’ or ‘grove of koki [Hopea odorata] trees’, stood here, the capital of the Khmer Empire referred to in historical sources as ‘Lingapura’. King Jayavarman IV, who presumably had some attachment to the area, moved the centre of his empire from the Angkor region, to which location it only returned in the reign of his son Harsavarman II. The large number of temples and shrines, and the densely packed archaeological objects to be found on the surface, as well as some of the surviving Sanskrit and Old Khmer inscriptions suggest that the significance of Koh Ker did not fade after the middle of the 10th century, but that it continued to be a regional centre (Plate 1).

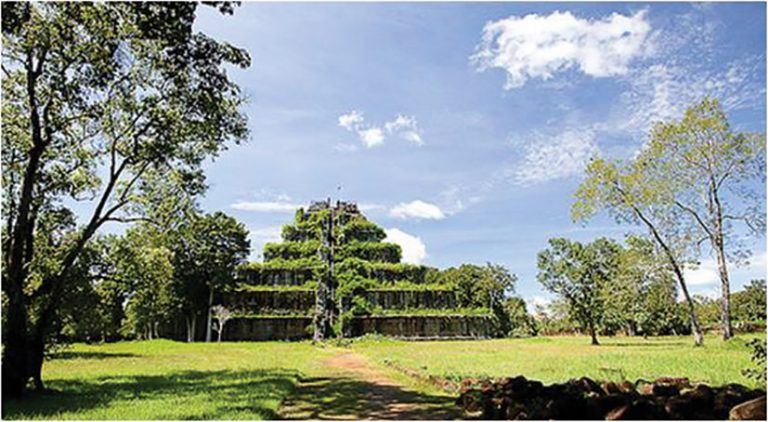

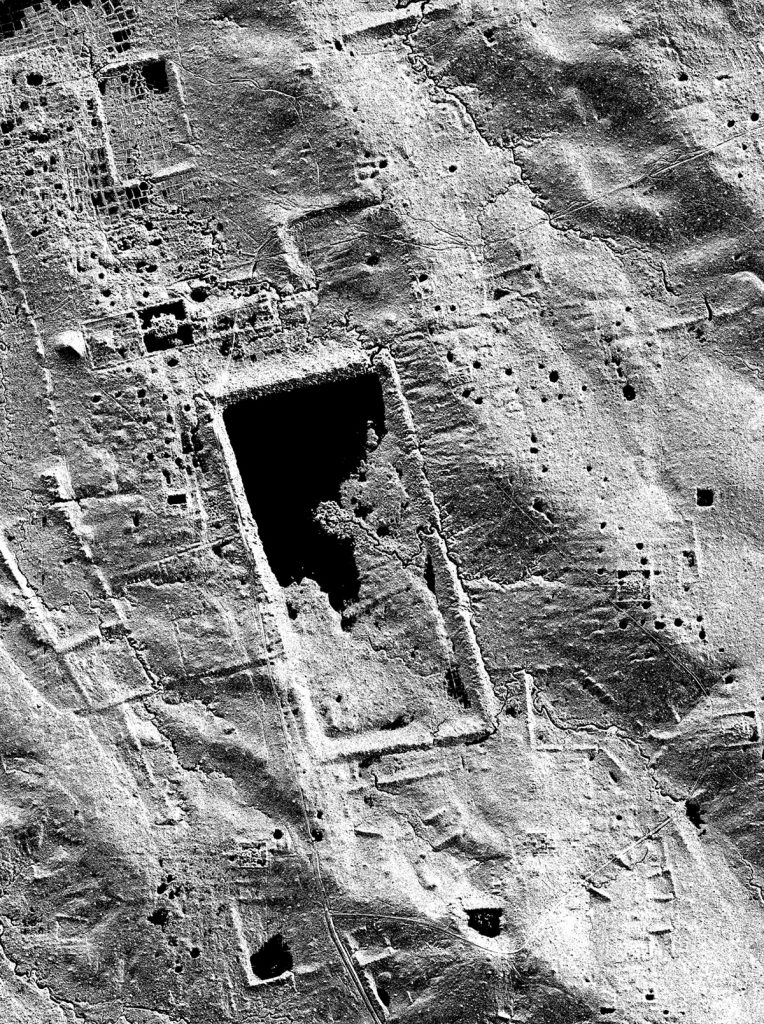

The characteristic, inner core of the historical settlement system covers an area of about 9km2 . Its central, dominant feature is a 1200 x 600 meter, rectangular reservoir known as the Rahal, and on a raised area to the east and west we find several characteristic groups of buildings. The central sanctuary is located northwest of the reservoir. Prasat Thom and the so-called Prasat Krahom ensemble with the whole ‘composition’ appears from the west to be completed by a seven-step, 36-meter-high pyramid dedicated to Siva—perhaps Koh Ker’s most famous building—the so-called Prang (Plates 2-3). The unique historical background alone makes the ‘ruined city’ very exciting, existing as it does in a special symbiosis with the surrounding jungle. At the same time, researching and preserving individual groups of buildings scattered over a huge area is a huge professional challenge. Within the entire protected zone, nearly 130 archaeological sites are known, including 54 extant temples. Consequently, in connection with a vast area rich in archeological sites and monuments, one must inevitably face a few facts before getting down to the real work.

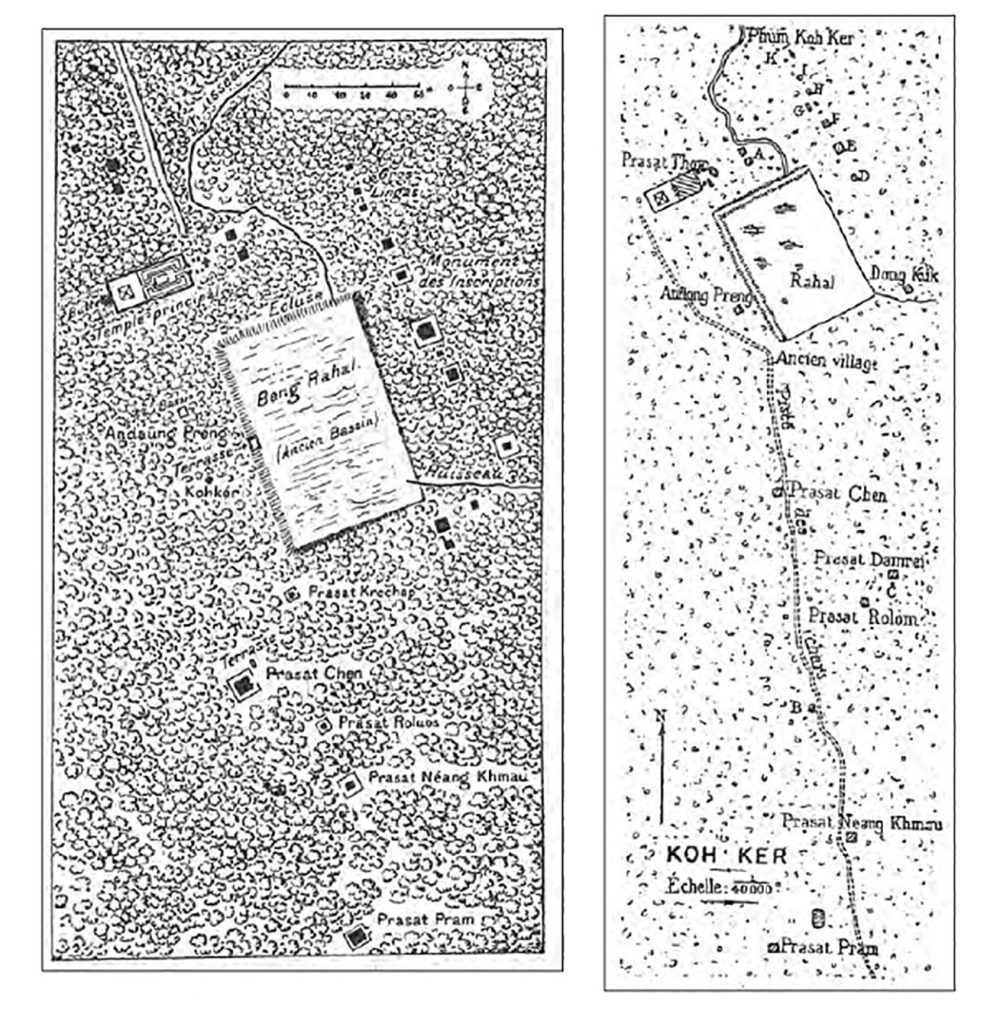

The conditions experienced by Louise Delaporte, Étienne Aymonier and Lunet de Lajonquière, who arrived in Koh Ker during the last third of the 19th century, are difficult to put into words. The rediscovery of the former royal capital obviously left a lasting impression in all their memories. However, in addition to the joy of discovery, even the first sketches of Koh Ker tell us about the systematic work into which French scientists submerged in order to describe these ruins at the heart of the jungle. The scientific research being carried out on Khmer high culture at that time was still largely about wondering at the relics to be found lying on the surface, and phrasing it in the somewhat old-fashioned thoroughness of the 19th century. What is more, there is no question that without the scientifically demanding survey of a city that has been deprived of its original detail, looking back over nearly a century and a half, we would be much worse off today. Many relics, sculptures and building remains, now exist only in this documentation, and today we look at contemporaneous sketches and photographs as if we were looking at the last representatives of an extinct, once prestigious animal species.

From the outset, this heroic enterprise has lost nothing of its former raison d’être and goals. Although our methods and tools have undergone significant changes in recent decades, now also the key to understanding Koh Ker’s serenity is to do nothing more than make a conscious inventory of the material relics. It is important to recognize that although research always promises significant results, using traditional archeological methods an area of this size in its entirety is virtually unexplorable. No matter how much effort is made, any number of more people would not be enough. At the same time, the rich cultural heritage of the area and its condition clearly require care and cry out for experts in research and restoration. Consequently, in addition to the extensive research ideas discussing the connections between the traditional census, the historical structures and the changes in the landscape, there is a special need for a direct connection with the individual ruin areas. You simply have to go there to see and feel the specific micro environment, atmosphere and ‘universe’ of each building. And as an archaeologist, I have to add that in order to do so, one must connect the known world above the earth with the unknown realms buried beneath the earth.

Obviously, a variety of goals flash before the researcher’s eyes here, but it is important to see at the outset that the exploration of a group of buildings is the beginning of a process at the end of which the area will be completely transformed. The goal is to create an ‘end result’ that can be visited by tourists in all its elements, similar to the familiar restored monuments in the Angkor region.

In this context, it is desirable to create pilot projects (small systematic excavations) that go hand in hand with the ongoing historical, art historical, epigraphic and topographic research that has been taking place since the end of the 19th century (Plates 4-5). At the same time, they offer a real opportunity to make the explored phenomena accessible, recoverable and visitable.

Although it might seem like ‘being clever’, for that very reason, even before the start of the research, we tried to select an area that was both promising from a historical and art historical perspective, but whose structural condition posed little danger in the environment of the excavation. After several seasons of field trips and on-site surveys, this was how the choice of Prasat Krachap was made, one of only 38 known in Koh Ker, concealing stele with 16 Sanskrit and Ohmer inscriptions, and unique with its five brick-built inner shrines.

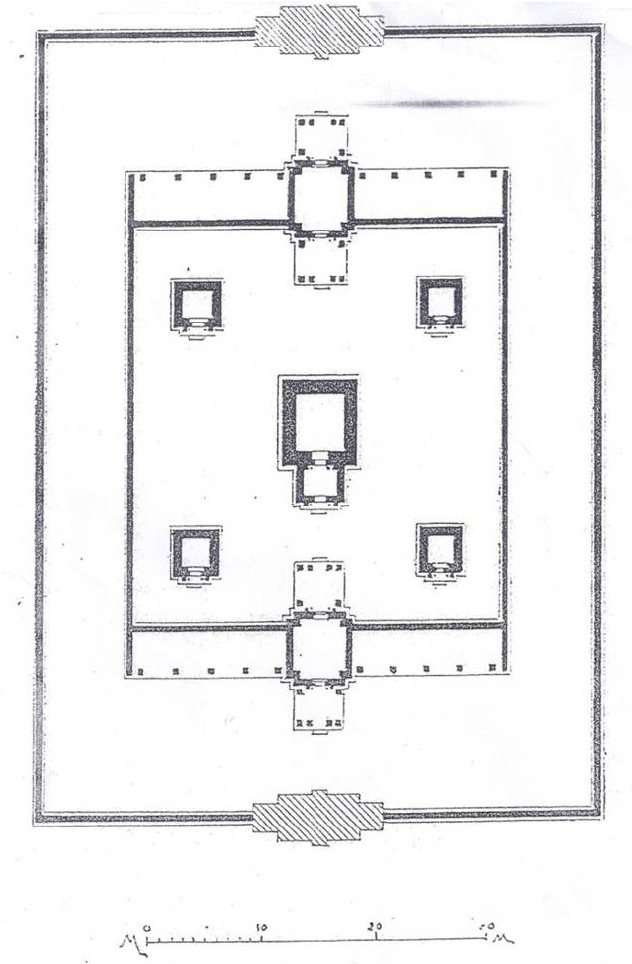

The shrine lies about 200 meters from the northeast corner of the Rahal, the overall orientation of the cluster of buildings is in line with the central shrine (Prasat Thom) but facing west in contrast to it. Due to its orientation, the currently known inscribed remnants from the eastern and western gallery pairs and shrines of the temple, presumably dedicated to Vishnu, impart little of the history of its construction. However, based on a fragment, its first period can certainly be dated before 928 (Plate 6).

Archaeological excavations in and around Prasat Krachap

In some senses, any exploration of virgin territories is destined for success. It promises previously unknown information, findings and exciting connections. And let’s be honest, Koh Ker offers countless such terrains. Sometimes, however, a methodical or cautious approach needs to be explained, just as the agenda developed in the research of Parast Krachap is characterized most by its careful planning; and not with regard to the challenging climate, unpleasant tropical insects, nights spent in the jungle, spiders, snakes and scorpions. Merely that the ends do not necessarily justify every means. Clearing a section of a building, the careful survey of the condition of a 10th-11th or 13th century structure in the area often takes us much further than the immediate, thoughtless stripping of the prestigious shrines and galleries in the hope of new inscriptions and sculptural fragments. In archaeological research also, everything has its place and time. Thus, the current results of the exploration should also be considered as initial steps. These are stations on a long journey that we all hope we will travel with our Khmer colleagues over the coming years.

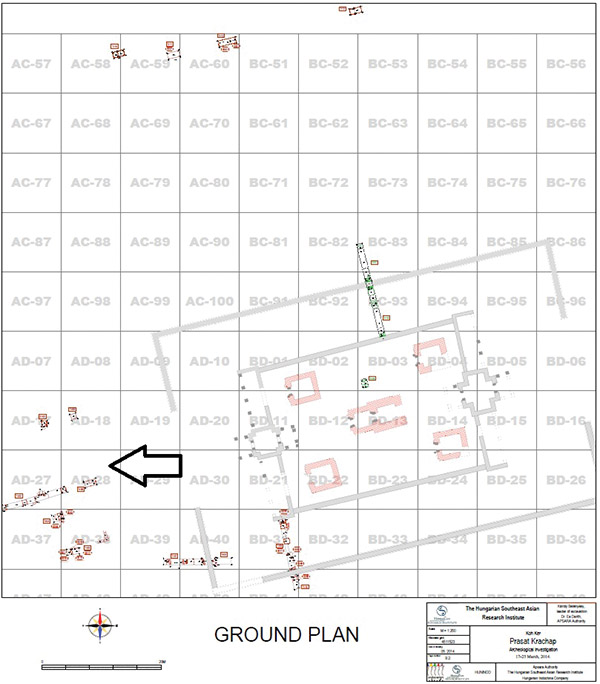

We tried to prepare the excavation with due diligence. Thus, we also examined the identifiable finds on the surface before it began. During the field trip, we searched approximately 12,000m2 of space in the area of the building group and in its immediate vicinity.

I must note that the extent of the former historical settlement system can be deduced from the finds on the surface, which was a complete novelty, but at the same time it showed very successfully that the characteristic built environment: temples and sanctuaries, had been at one time filled by an intensive settlement network, signs of which can also be found on the forest-covered surface (Plate 7). It should come as no surprise then, that the archaeological research carried out in 2011 and 2015 primarily sought to clarify the relationship between the building and its immediate surroundings, the unclear details of the building, and the chronological relationships. In the research sections opened during the excavations, we focused especially on such sensitive issues as the construction history of the building complex and the clarification of the ground plan, where salient differences from earlier work were apparent during the fieldwork.

With regard to the latter, identifying the pavilion that once stood in front of the western gate of the building group and was clearly connected to it was particularly important. Despite the fact that the stone elements presumed to be in the building had been covered with a large amount of modern waste material, the laterite blocks of the former base and ascending walls were telltale. After the removal of the layers of modern refuse, the most important details of the floor plan became evident; thus, the southeastern and southwestern corners in particular, as well as the western retaining wall and the former plinth level. Only minor details of the staircase identified in the east-west axis of the building were excavated, but the test pits showed that the southwest corner of the building and the details of the west wall of the building remained relatively intact beneath the surface (Plates 8-9). The identification of Prasat Krachap’s pavilion in the 1930s, which was not included in Henri Parmantier’s survey (Plate 10), also confirmed that the floor plan of the original building must have been much more complex than previously assumed compared to the identifiable ruin area on the surface. A much more sophisticated, colourful and detailed world began to unfold as we dug down. Consequently, with great enthusiasm, we embarked on the dual excavation of the exterior and interior of the perimeter wall of the Prasat.

Here, for the first time, we were able to obtain archaeological evidence that the building group had been constructed from the centre outwards, with the outer perimeter wall and the pavilion being built only in a later phase. The external structures were created following large-scale landscaping related to major construction, partly using the debris from the construction itself (Plate 11).

However, based on the stratification observed in the test digs, we were able to collect information about more than the structure of the buildings and the construction periods. Based on the relationship between the bedrock and the subsoil and the artificial granular laterite levels, we can reasonably assume that Prasat was located on an earlier natural elevation, a small hill. The central sanctuary and the buildings around it were built on this and their surroundings were artificially remodeled alongside the constructions. There was a significant level difference between the exterior and interior of the perimeter wall. Excavations revealed that the space between the wall surrounding the shrines and the perimeter wall received a significant covering. This interior filling, in which significant quantities of roof tiles and 11th-13th century ceramics were found, belonged to the original building layers and covered the roughly profiled plinth. From the covering, and especially from the large number of roof tiles, we can assume that in the history of the building there was a change during this period or immediately thereafter. Since no finds from later dates can be identified in the area, and a uniform layer related to the destruction or transformation of the group of buildings could not be identified either, it could be that the building became more or less uninhabited after the 13th century.

Given the excitingly promising results, the excavation took place in front of the south façade of the Prasat West Gallery. The aim was to study the relationship between the two phases, the internal building group and the fence wall construction. Although we already had some information about the internal stratification of the filled area between the two walls in connection with the research of the outer wall, we wanted to supplement this by observing the relationship between the two built structures and by collecting information on the possible construction periods (Plates 12-13).

During the excavation of the aforementioned area, we found, as we had in the previous section, that the Prasat and the original, profiled plinths of the fence wall were covered with a significant 70 cm layer of outflow. The probe managed to identify the original building layer, which can be dated to the first third of the 10th century, and the walking levels and phenomena belonging to the Prasat. Based on these, the earliest phase in the construction history of Prasat became increasingly clear to us. The earliest sanctuary was built on a small natural hill that rose above its surroundings. On the natural promontory, the surface on which the central group of buildings was placed was formed from laterite and sand layers. In front of the south façade of the gallery, we also managed to observe the construction levels connected to the plinth. We were able to identify two column locations in the section. Both are sited near the façade, and are sunk into the sand layer used for the foundation, but these were obscured by the walking levels after construction. Presumably, these could be directly related to the construction and we can correctly infer the remains of the former construction scaffolding. The construction level is followed by several walking levels. Narrow, hardened, stamped layers of Laterite indicate the long-term, continuous use of the building group. This layer was then overlaid, covering the lower, profiled layer of the plinth. The roof tiles and 11th-13th century ceramic fragments seem to confirm that during this period a significant change took place in the history of the building, the surface level of the area increased in the vicinity of the galleries and the interior buildings. Based on the roof tile rich excavation finds, this was in the 11th-13th century, although we do not have any other information about the origins of the filling, the finds suggest the transformation of the building, the destruction of the roofs, and the temporary or permanent abandonment of the building group. (plate 14). Which certainly concurs with the internal periods of the residential areas identified in the vicinity of the temple during the fieldwork and excavations (Plate 15-16).

However, based on the stratification observed in the test digs, we were able to collect information about more than the structure of the buildings and the construction periods. Based on the relationship between the bedrock and the subsoil and the artificial granular laterite levels, we can reasonably assume that Prasat was located on an earlier natural elevation, a small hill. The central sanctuary and the buildings around it were built on this and their surroundings were artificially remodeled alongside the constructions. There was a significant level difference between the exterior and interior of the perimeter wall. Excavations revealed that the space between the wall surrounding the shrines and the perimeter wall received a significant covering. This interior filling, in which significant quantities of roof tiles and 11th-13th century ceramics were found, belonged to the original building layers and covered the roughly profiled plinth. From the covering, and especially from the large number of roof tiles, we can assume that in the history of the building there was a change during this period or immediately thereafter. Since no finds from later dates can be identified in the area, and a uniform layer related to the destruction or transformation of the group of buildings could not be identified either, it could be that the building became more or less uninhabited after the 13th century.

Given the excitingly promising results, the excavation took place in front of the south façade of the Prasat West Gallery. The aim was to study the relationship between the two phases, the internal building group and the fence wall construction. Although we already had some information about the internal stratification of the filled area between the two walls in connection with the research of the outer wall, we wanted to supplement this by observing the relationship between the two built structures and by collecting information on the possible construction periods (Plates 12-13).

During the excavation of the aforementioned area, we found, as we had in the previous section, that the Prasat and the original, profiled plinths of the fence wall were covered with a significant 70 cm layer of outflow. The probe managed to identify the original building layer, which can be dated to the first third of the 10th century, and the walking levels and phenomena belonging to the Prasat. Based on these, the earliest phase in the construction history of Prasat became increasingly clear to us. The earliest sanctuary was built on a small natural hill that rose above its surroundings. On the natural promontory, the surface on which the central group of buildings was placed was formed from laterite and sand layers. In front of the south façade of the gallery, we also managed to observe the construction levels connected to the plinth. We were able to identify two column locations in the section. Both are sited near the façade, and are sunk into the sand layer used for the foundation, but these were obscured by the walking levels after construction. Presumably, these could be directly related to the construction and we can correctly infer the remains of the former construction scaffolding. The construction level is followed by several walking levels. Narrow, hardened, stamped layers of Laterite indicate the long-term, continuous use of the building group. This layer was then overlaid, covering the lower, profiled layer of the plinth. The roof tiles and 11th-13th century ceramic fragments seem to confirm that during this period a significant change took place in the history of the building, the surface level of the area increased in the vicinity of the galleries and the interior buildings. Based on the roof tile rich excavation finds, this was in the 11th-13th century, although we do not have any other information about the origins of the filling, the finds suggest the transformation of the building, the destruction of the roofs, and the temporary or permanent abandonment of the building group. (plate 14). Which certainly concurs with the internal periods of the residential areas identified in the vicinity of the temple during the fieldwork and excavations (Plate 15-16).

After a three-year hiatus, in March 2014, the aims of the resumed archaeological excavations were to examine the strata belonging to the construction history of the building group on the south side, as well as the previously opened trench, and the relationship between the building and its surroundings. Thus, in fact, we were able to obtain a complete north-south cross-section of the structure surrounding the shrine area of Prasat Krachap. In addition to data on the construction history of the temple, we also hoped for important information from the new digs due to the planned complete excavation of the ruin area, since during the post-excavation restoration we needed to adjust to the original ground levels which were covered with significant quantities of earth and building rubble. Their management, deposit, and possible changes in the statics of a temple building can significantly influence the planning of archaeological excavations and the restoration of monuments. Taking the latter aspects into account, we definitely wanted to supplement our previous knowledge with data from within the sanctuary area (Plate 17).

However, during the research, we were able to identify the building layers not only in the inner trenches by the wall, but also on the external side of the wall. A large quantity of household ceramic artefacts referring to the surrounding settlement were recovered from the embankment covering the former walking level and the ancient levels below it. At the end of the probe, nearly 6 meters from the outer enclosing wall, we were lucky enough to unearth an intact vessel as well (Plate 18). The pot had collapsed from the pressure of the ground, its wall was cracked, so we could not lift it out in its entirety. Its peculiarity lies in the fact that we managed to excavate it from the boundary of the strongly rammed, clay and granular laterite layer of the plinth, which had been formed prior to the construction. Thus, its age is presumably the same as the construction of the outer perimeter wall. Given that it was a reddish-coloured, slightly curved, single-edged, curved-bottomed, hand-made liquid container, a rough dating to the 10th-12th century cannot be refined. But it certainly bears the imprint of the hands of the people who once worked on or around the building.

To identify the original walking levels, we opened a smaller pit in the innermost sanctuary area, on the north side of the central brick sanctuary. In the 1 meter x 1.5-meter excavation pit, below the seemingly uniform layer of building debris, at a depth of about 1 meter -1.2 meters from the current surface, we were able to identify the original level of sandstone slabs, indicating that the original plinth levels and walkways may have remained in good condition under the debris covering the sanctuary area (Plate 19).

CHANGE OF ATTITUDE, CHANGES IN RESEARCH STRATEGY

As already mentioned in the introduction, the basis of the research and inventory of the area was the visible historical remains: the buildings, the unique artefacts (canals, dams and the Rahal). After progress in the discovery and identification, the research of the internal contexts and chronology of the area could arise for the first time. Which was built on a specific or a group of questions. The starting point of the research was none other than the defining character and built environment of the royal center to be built during the reign of IV. Javayarman, with special regard to the official sites, such as the royal residence and the surroundings of the central sanctuary, with the year 928 considered the origin. While historical, epigraphic, and art historical research has fundamentally sought to clarify this issue and its internal chronology. The development of Koh Ker into a ‘city’ has also become an attractive research goal, changing the urban environment, especially with regard to certain elements of the complex water management system.

From the outset of our research at Koh Ker, we decided to select a sample area because, in addition to the topographic research that typically focused on larger areas, we wanted to supplement specific information from the phenomena typically visible on the surface with specific archaeological data. We focused on one area in the archaeological excavation, and launched a complex archaeological program in the vicinity of Prasat Krachap. (The choice was obvious because the building has a wealth of epigraphic source material and was presumably erected from the point of view of architectural history during the construction of Koh Ker in the 10th century, and its size also makes it technically manageable). On the other hand, it became clear from the initial research that the individual building groups are not isolated units, but the nodes of a presumably rich but unknown settlement network. The large number of epigraphic sources, in addition to the few historical ones, referred to an extensive supply base and service-type settlements. So we were not looking for a building, but for an economic and spiritual centre and its direct supply system.

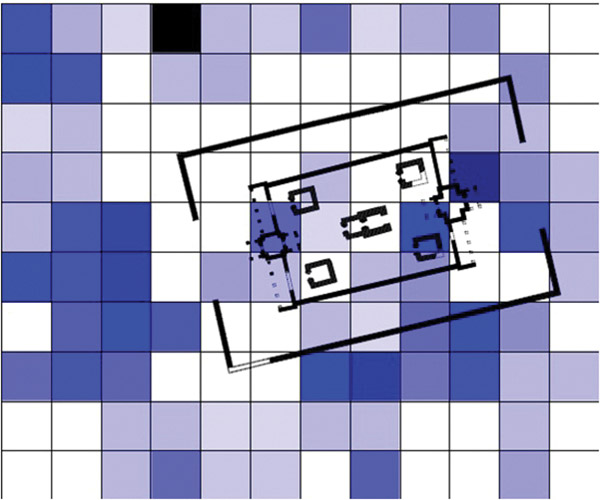

Although we did not expect many finds without intensive excavation, the results thoroughly refuted our previous assumptions. During the 2011 field trip, we saw traces of intensive residential areas in the immediate vicinity of Prasat Krachap, and in addition to the finds related to the temple, the surface finds clearly indicated a rural environment. Furthermore, the intensity of the finds did not end at the boundary of the designated immediate environment. The forest, which seemed untouched between the various temples, seemed to have in fact been a historically densely inhabited area. Fortunately, the beginning of our work in Koh Ker coincided with a great methodological change that fundamentally altered our assumptions about settlement history and archeology research. The LIDAR survey (see here Róbert Kuszinger’s article), which has been used as a starting point since then, because it made a clear breakthrough in the study of less perceptible anthropogenic changes. We could view this turning point as the start of a new era. The new survey method proved to be the true justification of our previous ideas about the historical settlement of the former jungle and the immediate surroundings of the temples. We have a huge amount of data in our possession that is still being interpreted today. How did all this affect our research around Prasat Krachap?

During the processing of the images, unique structures made of non-permanent material could be clearly identified that relate to the former settlements, partly in connection to the groups of buildings or aligned with the walls, the historical road network and the former planned water management. From this point of view, great importance is attached to the identification of unique, often insular forms, individual buildings, plots, or reservoirs associated with the plots, which can also be linked to archaeological research. After all, the direct archaeological evidence of this historical settlement layer, identified by remote sensing procedures, is the rich discovery of the formerly densely inhabited area outside the outer wall of Prasat Krachap. Here, the archaeological find is not only confirmation of the former settlement, but also provides a clear chronological basis for interpreting an anthropogenic environment that is clearly identifiable in terms of space and relationship systems (Plate 20).

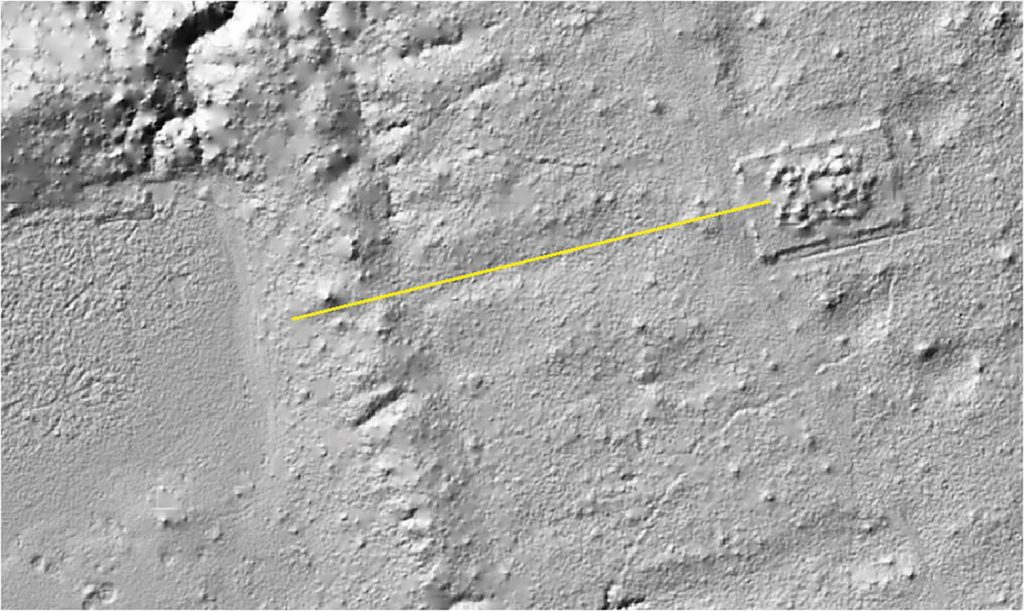

Continuing the above line of reasoning, it seems rational to conclude that the anomalies on the basis of which we can deduce the differences between the individual settlement layers may indicate chronological differences, and in these several construction periods or even the abandonment of certain settlement parts can be suspected. We do not have any archaeological evidence for this as yet, but due to identifiable characteristic forms in the vicinity of Prasat Krachap that indicate changes in settlement, we have extended the research to these areas as well. Therefore, in possession of the available data, a linear path (?) structure passing through the east-west axis of the temple came to our attention (Plate 21). Based on the recordings, it seems that this main direction could be decisive in terms of the former settlements around Prasat Krachap and clearly connects the temple with the central reservoir, the Rahal. The anthropogenic nature and structure of this east-west aligned linear system was also striking on the LiDAR readouts. In 2011, we managed to uncover a building opposite the east gate of the temple, as well as the remains of a pavilion on its axis, and a staircase towards the Rahal. We therefore assumed an earlier, official relationship between the reservoir and Prasat Krachap, the identification of which we had begun even in June 2014. Although the vegetation period was not conducive to fieldwork, in the forest between Prasat Krachap and Rahal we were able to identify the remains of an official road 180 metres long and nearly 5 metres wide lined with laterite blocks. In some of the large laterite blocks, postholes were identified that had been carved for wooden columns. At the junction of the road and the west bank wall of the Rahal, the design of the terrain indicated a built-up terrace, near which we also found the remains of a carved sandstone lion (Plate 22). During the field trip, we tried to examine all traces of anthropogenic intervention outside the road line. As a result, near the temple, slightly farther from the axis of the road, some traces of quarrying were discovered on a sandstone surface (Plate 23).

After that, we initiated further excavations in March 2015 with the intention of examining the details that had been identified with LiDAR processing in 2014, and to obtain information about the surface evidence of the quarry.

The research began at the supposed junction of the pavilion near the entrance and the road to Rahal, where small fragments from a sandstone lion appeared on the surface. On the northern side of the ditch we found laterite kerb stones, displaced from their original location, at a depth of about 20 cm below the surface. On the south side, after documenting the surface fragments of the lion, further deepening the trench, we managed to excavate and following excavation lift the larger surviving block of the body of the lion, which presumably originally adorned the stairs. The body fragment was actually found at the original walking level. Here we also managed to unearth a small area of the original pavement surface of the road. Accordingly, the road, which was based on sand, clay and laterite granular layers, sloped slightly to the south and was about 4.8 meters wide, and was paved with irregular sandstone slabs. This confirmed our previous assumptions, since during a field trip through the woods we had found several irregular sandstone slab fragments where fallen trees had disturbed its original structure that we conditionally linked to the original pavement, but the first clear evidence we found was during excavation of the original layers and the original walking level (Plate 24). The road is closed by a large terrace close to the Rahal, the area of which is almost completely overgrown with forest, so any substantive study would also require the felling of large trees. However, during clearance of the shore wall from the terrace in the direction of the Rahal, we were able to expose the remains of the original shore wall and staircase stacked from laterite blocks (Plate 25).

The excavation of a quarry discovered just 40 meters from Prasat Krachap produced some interesting results. Traces of the cutting of four 50×150 cm stone slabs from the original sandstone surface and the preparation of two more of similar size blocks for cutting were identified. We were also able to discern marks left by the metal mining tools that had been used in cutting the blocks out of the sandstone. During the excavation here, it also became clear that this quarry had been abandoned following completion of the quarrying process and was then systematically reburied. The grooves sunk into the stone were buried with the same layer of laterite granular, partly mixed with roof tile fragments, which were identified several times during the excavation of the road and when the foundation layers of the buildings were examined. The carefully planned and hard-packed layers suggest that the scarring of the landscape caused by the quarrying associated with the construction of Prasat Krachap but was reinstated when the construction was complete. Although it is only a small addition, added to previous excavation results the quarry is also testimony to conditions in the local environment and the usability of local resources, which had possibly been important considerations in the selection of the location of each shrine (Plate 26).

After all this, it is right to question whether any general conclusion can be drawn. Well, in fact, there are and there are not. This is not an indication of the ineffectuality of the excavations, but rather specifically represents our belief in the future. After all, the key to archaeological research in Prasat Krachap, or Koh Ker, is continuous and reliable work and close collaboration with Khmer colleagues. The partial results are exciting and often stand on their own, but the general lesson from recent archaeological discoveries is how the image and research strategies for Koh Ker have been transformed by modern remote sensing results and, at the same time, how research has evolved toward the hitherto unknown settlement history of Koh Ker. Knowledge and use of LiDAR data has become a clear starting point for the results to date and future research. At the same time, the historical image of Koh Ker and the possibilities for interpretation have expanded. Thus, today we have to imagine the formerly significant settlement increasingly as a special settlement network. Research has previously focused on the main details of this network, individual temples and visible phenomena, but the areas between the main nodes of the network have remained obscure. Thus, the intensive system of connections (roads and water system) and the structures surrounding the temples (such as settlements or industrial activity), their connections were unknown. Yet these details are of great importance in understanding the creation and function of the area (Koh Ker). Perhaps we can more accurately draw and interpret the extent and nature of the transformation of the natural environment, the way the area was settled and populated. In this work, remote sensing and archaeological excavation go hand in hand. Thus, there is no question of abandoning our traditional excavation methods, since we can only hope for the chronological underpinnings for our current ideas, as well as epigraphic data, from archaeological finds. However, in addition to scientific studies and low-intervention sampling, large-area systematic excavations offer the greatest opportunity to learn about what lies beneath the surface of Koh Ker. The narratives of art history, epigraphy, and historical science are quite simply exhausted. Which is why we have to give increasing space to archaeological excavation and carry out a conscious and systematic sampling programme, such as the excavation in the vicinity of Prasat Krachap.

Recommended reading

Belényesy, Károly – Ea, Darith 2011. “Preliminary Report on the Archaeological Survey at Koh Ker, Prasat Kracap.” In: Kuszinger, R. (ed.) Koh Ker Projekt, Interim report for ICC TC 2011. Budapest: HUNINCOR, pp. 5−16.

Belényesy, Károly 2013. “Report on Archaeological Research Work in the Precinct of Prasat Krachap at Koh Ker” In: Renner, Zsuzsa (ed.) Archeological Mission at Koh Ker, 2011. Budapest: Publications of the Hungarian Southeast Asian Research Institute 3, pp. 19–24.

Evans, Damian 2013. “The archaeological landscape of Koh Ker, Northwest Cambodia.” Bulletin de l’Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient 97/98 (2010-2011): pp. 91–150.

Sipos, György – Tóth, Orsolya – Belényesy, Károly – Bozsó, György 2013. “Thermoluminescence Dating of Pottery fragments from Koh Ker, Cambodia” In: Renner, Zsuzsa (ed.) Archaeological Mission at Koh Ker, 2011. Budapest: Publications of the Hungarian Southeast Asian Research Institute 3, pp. 72–86.

Jacques, Claude 2011. “The Prasat Krachap” In: Kuszinger, R. (ed.) Koh Ker Projekt, Interim report for ICC TC 2011. Budapest: HUNINCOR: pp. 3–4.

Belényesy, Károly 2015. “Archeological Investigations in Koh Ker, Prasat Krachap Temple and Surroundings, 2014–2015” In: Róbert, Kuszinger (ed.) Koh Ker Project. Annual Report 2015. Budapest: Hungarian Southeast Asian Research Institute, pp. 8–35.

Kuszinger, Róbert 2015 “Lidar Data Application at Koh Ker” In: Róbert Kuszinger (ed.) Koh Ker Project. Annual Report 2015. Budapest: Hungarian Southeast Asian Research Institute, pp. 81–106.

Parmentier, Henri 1939. L’art khmèr classique: Monuments du quadrant Nord-Est. Paris: Publications de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient. [vol. XXIX bis].

Wickery, Michael 2001-2002. History of Cambodia. Summary of Lectures Given at the Faculty of Archaeology. Phnom Penh: Royal University of Fine Arts