Volume 1, Issue 3, July – August 2020.

At the Roots of the Art of

Sopheap Pich

An Interview with Sopheap Pich by Reaksmey Yean-Georges

“My technique is almost so simple that they shouldn’t call it a technique,” sculptor Sopheap Pich talks about the formulation of his works as we sit beneath a tamarind tree discussing his career; strong waves of warm, heated wind push in at intervals, while the artist sits on a wooden stool with his legs crossed, cradling a mug of tea in his lap. Known for his use of bamboo and rattan, materials found in abundance in tropical Cambodia, Pich maintains that his intricate and strenuous sculptural beings are not intended to “show any complications,” but to just simply “create form”.

While Phnom Penh bids its final farewells to that icon of the Royal Ballet, the late HRH Princess Norodom Bophadevi, I have travelled thirty kilometers northeast of the city on National Road 6A to Pich’s studio-cum-residence in Prek Anh Chanh village. Once through the two-hectare property of reclaimed rice-fields, now covered with luxurious, tropical woods, one can hear the cackling of birds every now and then. Compared to the chaotic traffic and noise of Phnom Penh, this place is like a retreat. I feel as if I am in the temple of God, a place where I can find solace and beauty. This sense of ‘quietude’, as Pich would describe this environment, provides the artist with a “chance to think, and my team the opportunity to work without interruption, not 100 percent, but 90 percent, which [is something] we have never had before.” Prior to this abode, the artist had previously moved at least eight times since he repatriated to the Kingdom from the United States in 2002. When asked what difference this place makes, Pich remarks that “in Cambodia, there are many things that are distractions: cultural events, daily life activities, accidents, fighting, traffic. Most of that stuff is outside now; this is the first time that we have this opportunity.”

It is this level of concentration that one witnesses when one steps into what I call “the sanctum sanctorum of creativity”, a hall in which Pich and his team realize and formalize the artist’s imagination. Housed in a white-concrete building situated on the eastern edge of the property, this hall is surrounded by trees that are taller than it is. Once he has dropped me off at its main entrance, my rickshaw driver searches for some shade to take his afternoon nap while he waits to take me back. I immediately march in, a group of Pich’s assistants are busily stretching and patching up new works, it seems like no one notices my presence—maybe it’s because I have got my afro bundled up like the Buddha’s ushnisha (topknot) today. I politely interrupt one of them and ask for Pich’s whereabouts. They point to the far end of the room, to my left, where I see Pich, in a light-coloured t-shirt and Khmer-style baggy pants, standing against the oven mixing some wax in a burnt pot. As I approach, the artist turns around and says, “give me a few minutes, brother.” This act of cooking and the medium used to serve this purpose have been described by Pich as “the poor man’s cooking material, the refugee experience, the Khmer Rouge experience. This is poverty, and in that way, I’m seeing my own history in that, but it is not obvious, you wouldn’t know that if I didn’t tell you.”

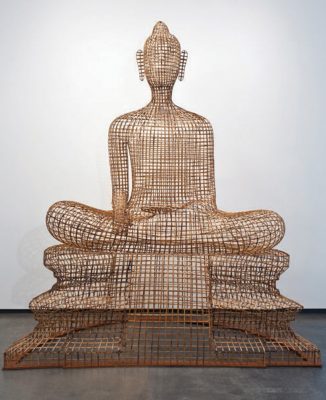

The first of five sons, Pich Sopheap, was born in 1971 in Koh Kralaw, Battambang Province, in northwest Cambodia. In 1979, as the Khmer Rouge regime collapsed in the face of the advancing Vietnamese army, his family, like so many others, escaped to a refugee camp across the Thai border. In 1984, when he was thirteen, his family settled in Massachusetts in the United States, where he went to school and university. After a few loose years of travelling and working at a variety of different jobs, he finished his Masters of Fine Arts at the Art Institute of Chicago, and in 2002 returned to the country of his birth. Today, Pich is a leading international artist and is often described as the only Southeast Asian artist to ever have showcased a solo exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, where his Buddha 2 (2009), an unfinished Buddha figure that trails off into dangling strands of ratan, is on permanent display in the gallery of Southeast Asian art.

RY Bong (older brother), I want to begin by asking about your little forest, what can you say, especially to those who’ve never been here, about the atmosphere of this location, and of course the trees?

SP Yes, I plan all the trees. Nature, for me, is where I find solitude, where I find comfort, and where I find my forms. I think that the more time I spend looking at fruit, flowers, leaves, the more time I spend trimming the branches, the more time I spend learning about how they grow, about the distances between one tree and another, about how I can grow the seeds [the better]. I do collect seeds, and I propagate them. As you can see in the ones near us here. [He points to the row of propagated rosewood trees a few metres away] I see how they grow. I get to see what the inside looks like. I get to see what Mother Nature has programmed or, let’s say, actually created. I don’t plan a lot of fruit trees. I don’t know why that is. I guess I don’t eat a lot of fruit. I plan a lot of luxury wood; I plan a lot of Beng (rosewood), Neang Noun, Kranhong and Kakos (the Leguminosae family), Koki (the Dipterocarpaceae family). These are used as wood in Cambodia and a lot of people don’t know what these trees look like or what they’re called. I get to see what the seeds look like. I get to see what their fruit looks like. I get to see what their flowers look like. All of that is very important to me, and some of them become my work, such as Beng which has become a very big part of my life in the last four years or so. I think the more you think about nature the more ideas you can generate, it keeps me away from politics.

RY While nature has Antoong-ed you to find forms, or should I say, materialize forms, I wonder what Antoong-ed you to repatriate to Cambodia after a twenty-three-year absence? Antoong is an intriguing Khmer word that means to convince or persuade, or something like a magic spell that gravitates or summonses, and/or simply inspires.

SP It’s an interesting question; I get asked that a lot, and at different times I have answered differently, but I think it’s because when you get older, you understand a little bit more, maybe. I think no matter who you think you are, [it is] where you are born, where you spend your early childhood, that makes the greatest impression on you. It’s the longest, most enduring memory. [For me,] the memory of here was the strongest, obviously, because of the Khmer Rouge. If I had been born in Paris, I’d have had the calling to go back to Paris, but the Khmer Rouge was like living inside a vacuum, in a bubble, and some people had a really bad bubble. My parents had a horrible bubble. My bubble was not so horrible that I didn’t want to come back. So, as a child, you find that what you’ve done as a little kid remains as a very strong memory. I think that’s why I came back, and plus I just love the idea that I love Cambodian music, I love Cambodian food, I love Cambodian people, I love Cambodian beauty, I don’t love all of it but I love a lot of it. I want to be around my kind of people. I don’t know…

RY Can you describe the first impression, feeling, or experience of arriving at your long-lost home?

SP You know, I arrived on Independence Day, November 9. I had just had my 17th-anniversary party here with my five friends, which is interesting, a kind of beautiful sadness. What I found was that, at first, it was beautiful, but it was very depressing. I couldn’t talk for a few days. I couldn’t really describe anything because I had just come from Boston, and the flight was like a 24-hour flight, and then I landed in this country completely broken. It was 2002 and it was tough, it was emotional, very emotional. I remember the day was very bright, like today, hot and bright, but I remember the people looked very different from what I was used to every day in the US. There was no traffic at the time, there were a lot of motorbikes, no cars, really no cars, just a few taxis, old Camry. Along the side of the road, you could see houses with Khael, and it was dirty, it was just a mess, broken, dusty, desperate. In that sense, it was very sad. I felt very emotional about that. But, you know, I was also a broken person when I was in Boston, I was not happy. I didn’t have a chance to make my art. I didn’t have time. I was working all the time and struggling to pay rent.

RY You said that your struggle and your busy-ness in Boston did not leave you time to practice your art, and yet when you returned to Cambodia and encountered different struggles, it did not discourage you from pursuing a career as an artist here in Cambodia. Why was that?

SP I made a decision to be an artist a long time ago, when I was a student, even before I became an art major, but as a child of a refugee, it’s very difficult to see the possibility of being an artist because everything is against you, everything. Plus, historically, you are from Cambodia, it’s like, who are the artists? You don’t have anybody, there are no artists, you don’t see any role models… in any museum around the world. Where are the Cambodian artists? You never see them, you know, so everything is against you. Your parents are working in the factories and so how are you going to be an artist when your parents work in a factory? 12 hours a day, six days a week, just to make ends meet. They want a better life, and to be honest, to be an artist is not a good choice. I wouldn’t recommend being an artist to anybody. That’s why I’m not a teacher. I’m not a good teacher. I’d just help people to quit. I wanted to be an artist. That’s why I came back.

RY While you might help others to quit, you did not quit yourself, although you did struggle for the first few years of your artistic career in Cambodia. Evidently, today, you have established yourself as an internationally renowned and well-respected artist. Not to mention, if I may point it out, that you have also been reclaiming Cambodia’s place in world art history, especially through international displays and museum collections. My question is, what prevents you from stopping (or should I say, what keeps you going)?

SP Yeah, I found sculpture! It’s what gave me happiness, or whatever, was it success? Let’s just call it happiness, I don’t think it was happiness, but it was something [that was] more than everything else. When I found sculpture, I just knew that this is what I’m going to do, that I’m going to make big sculptures, I’m going to make strong sculptures. I’m going to make my sculptures and I’m going to be okay. RY I believe it was in 2004 that you ‘found’ sculpture, as you put it. But it was more than just sculpture, and it was also its materiality, the use of rattan and bamboo, which became your signature, if not your technique or style. Would you say it was the major turning point in your artistic journey?

SP Absolutely! Because I was finally, actually, making an object for the first time instead of making the illusion of some space or something, something that I can hold, and that made me feel like my time had been well spent.

RY Could you think of any project, or piece, that set you to become, to borrow Han Belting’s word, a “global artist”?

SP There isn’t any one piece, it was just time, like plowing a field. There’s a big field and you have a plow, you have a couple of Buffalo pulling that flat plow, Pachur Sre, you understand? You’ve got one blade, a small blade, but you have a huge hectare of land to plow. So, you start from here, you come back here, you go there, you come back, you go like this, and then the whole hectare is plowed [he gesticulates while explaining]. Then, you plant the rice, you take care of the bugs, the insects, you [irrigate], you keep feeding the plants, you take care of the plan, to come back every day, you [irrigate again, or drain]. That’s the journey, and a few months later, you get the rice. So, this is several years later, you get the name or whatever, but it wasn’t a plan. I didn’t know what was going to happen. I wanted it to happen, of course, but I didn’t know that was going to happen, but there was no other direction, there was no other choice, but to go forward.

RY In all this journey of repeated actions, what would you consider [to be] the most celebrated events, or should we say, the biggest breaks in your sculptural cultivation, so to speak?

SP There have been so many breaks, but one of the biggest was probably my residency in Norway in 2006. I was down and out. I was poor. I was alone. I didn’t have an assistant. I didn’t have a girlfriend. I didn’t have a dog. I didn’t have anything. I mean I was living in this little wooden shack for $30 a month. I had to come up with the rent. That was already very difficult. I was working with bamboo inside this little house and three Norwegians came and said “Do you want to spend a couple of months making a few sculptures, put on an exhibition at this gallery, we’re not famous, we’re not big, but we’ll pay for your flight, feed you, we’ll give you some money to live and eat. That was the biggest break at the time, I mean, can you imagine? I had absolutely no money! They took me away for two and a half months. When I came back from Norway feeling refreshed, feeling empowered, I had made some works there, sold a few pieces, and made a little bit of money. I came back and got Toma [the first assistant] to come back to work with me again.

RY Let’s turn our attention to bamboo and rattan. When did this all happen? How did you find the materials (or how did they find you)?

SP Having nothing, that’s what causes [things] to happen, you have to make something. I’m not a conceptual artist. I’m not a smart person that can just take a chair, put it on a table and call it a sculpture, so I have to produce, I have to make something. I had to make something because the only way to see anything is to make it. For me, because I didn’t have any skill as a sculptor, I didn’t have any money to buy any tools or to commission a stone carver or whatever to work for me. Rattan was across the street from where I lived, people were making furniture. I thought, well, if they can make furniture, why can’t I make sculpture? That’s how it began.

RY A lot of writing or literature about you has stated that the idea of using rattan and bamboo is derived from the fact that you saw or helped your father to craft some fishing traps when you were young: childhood memory. And since you mentioned earlier that “where you are born, where you spend your early childhood, that makes the greatest impression on you,” would you then agree with this characterization?

SP I helped my father cut wood or I helped my father, you know, make some fish traps and things like that. What you learned when you were five/six years old, you have a memory of it, but you have no technical skill. That’s why in my work there’s no skill. I don’t know how to weave or anything like that. My work is really, very simple. Well, it takes a lot of patience and it takes decision-making, but it’s a very simple process. Actually, my technique is so simple they shouldn’t call it a technique. It’s not like I do it differently here and I do it differently there to show any complication. It’s really just to create form. This is the simplest way!

RY You seem to describe this discovery, if I can call it such, as something [that] emerges out of the blue rather than [something that is] carefully planned. However, [from the outset], you have embraced this material, have had it formalize your imagination and history and, to put it in other words, to have it write your (hi)story. What meaning did you create throughout this journey?

SP I don’t know. It’s a bad habit [we both laughed loudly]. I like to let it go, I mean I’d like to do something else. I’m always trying to make things from other materials, but I always come back to this. I think through this process, it makes me see another way of doing something, but I adopted it very slowly. You can say that I’m comfortable using this material in a sense. I am quite comfortable with it now, it’s only been 15 years, so I guess I should feel a little comfortable, but I’m not tired of it. It’s like asking an oil painter: why are you still painting with oil after 30, 40 years? What else am I supposed to do? That’s what people do.

RY You talk a lot about your work as an imitation of form. However, from 2004 until probably 2013, your work has very much explored the concept[s] of memory and your personal history, and autobiographical accounts. Only in the later works, it seems that the focus has shifted. Would you agree with that (and why is that)?

SP It’s a just part of the journey. [My] last works for Tomio [Koyama Gallery, Tokyo, Japan], are a kind of form, but also, they referenced pain to me. So, if you’re making a painting, I think it’s very hard to get away from the kind of story because, you know, a painting is an image of something, it’s a recognition of something. So, how I use it, like how I learn to see my biographical memory, my biographical association, let’s say, in my work, it is in the material. I’m using aluminum, these are crushed aluminum, like from pots and pans, and this is the poor man’s cooking material, this is the refugee experience, this is a Khmer Rouge experience, this is poverty. So, I’m using those again, we’re starting to use those in my own art, but it’s subliminal. I use the material, it’s a used one and then I get it from Et Chai, a recycling place, and then clean it up a little bit. [It’s] reclaimed material, so in that way, it’s like I’m seeing my history in there, but not obvious, you wouldn’t know that if I didn’t tell you. When you see the new work [at Tomio], it’s reclaimed wood, old furniture. I’ve been collecting, my studio is full of wood, old wood because I love the beauty of it, the history, and just the word history alone is enough for me. I don’t care who’s history it is, and it doesn’t matter. I understand these things are historical so that carries some significance. So, a lot of what I do is just natural. It’s just what I collect, what I like, and I try to make sense out of it.

RY Thus far, what exhibition or project would you say you like the most?

SP Let me think for a bit, I have never thought about that [He takes a sip of tea]. I think my first one was at the French Cultural Centre [2004, Phnom Penh]. That exhibition was basically from the encouragement of the director of the centre at the time.

RY I don’t know if you realized, but recently, I came across a Wikipedia article about you in which it states that Reliefs (2013), Morning Glory (2011), and A Room (2014) are your major works. Do you think that is correct?

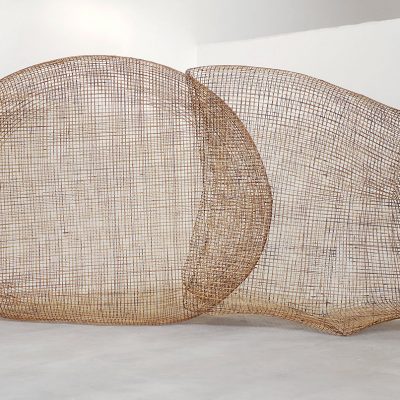

SP That’s pretty close! I don’t think A Room is a major work. It’s a big work, but it’s not a major work of mine. Morning Glory is a major work, A Room is more of an installation, a site-specific, and I’m not a site-specific artist. I don’t go to a site and say I’ll make work for that site. I make work in my studio.

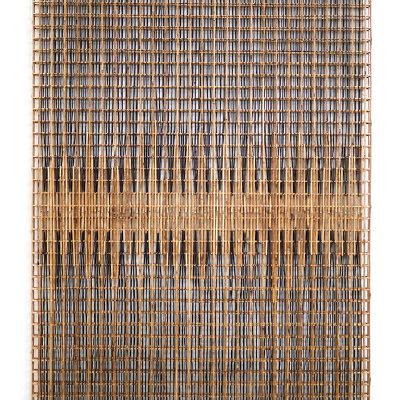

RY What’s about The Relief?

SP The Relief was recognized first by Documenta, by Carolyn (the curator of Documenta 13). The Relief was a major work because it was my turning back to painting, going back to where I started, but I found my way with painting. I was building a painting and not making imagery. I wasn’t worried about the image, I was still thinking [about] an object so in that sense, I feel like okay, I’m just approaching painting, but in my own way, as a sculptor.

RY Would you say then you have redefined the concept of painting?

SP No, I would say that I found my own way of making a painting as a sculptor [He pauses a few seconds]. And I still do it. I haven’t given it up. Just now, it’s in wood and cowhide and aluminum, and it’s still flat, it’s their relief, but it’s removed from the old relief, it’s another flaw, and it’s another type of really good continuation.

RY I believe one of the earliest breaks in your career was also a commission of two gigantic works at the Seacourt Plaza University Campus by King Abdullah University in Saudi Arabia. Although the pieces were originally designed in rattan, they were cast in bronze by UAP’s Brisbane foundry. Are you planning to make any bronze works in the future?

SP Yeah, but we won’t be casting it. We’ll be building it like bamboo. Casting is too much waste, a lot of waste, a lot of sand, a lot of burning. We’re going to build it, which is to say we buy strands of bronze and we’re going to beat it to get the kind of thickness and the character that we need, and then we’re going to bend it, and we’re going to make something better.

RY Recently, your works have been included in Minimalism: Space. Light. Object. at the National Gallery Singapore, an exhibition that explores the history of minimalism and recontextualizes its historiography by critically situating Southeast Asian art within this global context. Although it is an attempt to decolonialize art history, it is nonetheless, framing your work or the exhibition in a specific category and [mode of] philosophical thinking. Do you think your work should be conceived as such?

SP I think it depends on whom you ask nowadays; because of minimalism, the term itself, I think, as defined in the 70s. The word itself was arrived at through the few artists that were working [on it], like [Kazimir] Malevich or Donald [Judd]. If you look at the history of minimalism, you see those artists, so that that term was born out of those artists. I don’t want to claim that I’m one of them, I’m certainly not Donald Judd but I am inspired by Donald Judd, and I think Donald is inspired by the philosophy of reduction, less is more, and I also identified [with that in] my way of making. So, I think it makes sense that they call me and include my work in their minimalism show. The sculpture that I put in the show is of a shipping container, there are two of them, but it’s still two shipping containers, it’s not a shipping container with an object inside of it, it’s just a raw presentation of the shipping container: the form of it. So, you can say that my shipping container, what’s inside it is just air and I think the shipping container can be seen as a very minimal object if you look at some other artists like Sol LeWitt, who makes these rectangular or cubic cubes and he constructs them together and they look like a grid, three-dimensional grid on the floor or wall drawings, quite busy, but the mentality is a gesture, one gesture. I think that my container, my attitude towards the container, is the same, it just looks busy, but it’s just one gesture, it’s bamboo and wire. I tried together with the metal wire, and I tried in one way, it’s a system throughout. I don’t patch it up. I have no colour.

I have nothing. It’s all as if everything is there. I think in that sense, it makes sense, but I’m certainly not a minimalist by strict definition. I’m not a minimalist artist, there’s a part of me that is, but that’s not what I call myself. Not that I care about calling myself anything, just a sculptor, and I am just an artist who makes sculptures. There’s no need to fight for this movement anymore, it’s over. The movement is over. Now it’s just the individual.

RY One more question, before the last. You seem to have a lot of antiques in your study and studio, especially these Buddha sculptures and figurines. Why do you collect them (and how these inform your work, if at all)?

SP To be honest, I don’t know how much it does. I love anything old, and I love more and more Cambodian things. I think there is something about recognizing something in it, it could be like an old ceramic, which I have a lot of, it could be an old tool, it could be jewellery, it could be statues of Buddha, and I used to shy away from that stuff because I’m not religious. So, I don’t just put my boot around. I don’t burn candles. I don’t burn incense. So, I think it’s just part of us, of you and I, we are responsible for keeping these things around. These old things, if you don’t take it, somebody else will take it. This is true, it’s always the case, so it’s a guardianship. So, am I inspired by them? Absolutely! I mean they’re beautiful things, artists should be looking at beautiful things like that.

RY Finally, I believe you have probably read a lot of articles and profiles on you, and about your work. In your opinion, what do you think is missing or off?

SP It depends on who writes it, and it depends on how steeped they are in art history or culture [He pauses and takes a deep breath and sip of tea]. Oh well, okay technically they call my method weaving, I think that’s not at all right, if it’s metaphorical, like I weave history or something, but not technically. I think people get that wrong. The other one that people get wrong is that I escaped the Khmer Rouge. Nobody escaped the Khmer Rouge, though maybe some did, but I certainly didn’t [he laughed at the irony while speaking]. I escaped Cambodia. I escaped after the Khmer Rouge was finished. I escaped Cambodia, so I wanted to get the hell out of this country. I think this is a common misunderstanding. That’s just fact. It’s just factual information. I think I’m not trying to correct people. I’m just saying this is the fact. The fact is we live through the Khmer Rouge and we left after the Khmer Rouge ended. That’s a fact! If it’s about my work, that I design something and then I go to somebody’s workshop and hire the craftsmen to make it for me. This is far from the truth. My studio has nine assistants and we all do different parts of the work together. I do my part of the work, and they do their part of the work. We all have a different kind of responsibility. It’s very organic. I don’t predesign everything. Now, I’d make some scale model, but I usually don’t do that either, I draw on the floor, you usually don’t see it, after the project is done, we slip it out. I don’t hire professionals to make my work for me; I never have.