Volume 1, Issue 5, November-December 2020.

Gemstone Animal Talismans

in Burma

by Dr. Susan Conway

This article features animal talismans from the collection of the Zelnik István Southeast Asian Gold Museum in Budapest. They originate from Upper, Middle and Lower Myanmar (Burma) and are dated to the BronzeIron Transition Age (900 to 200 BCE) and to the Pyu Era (200 to 1000 CE) when Buddhist culture flourished in the Irrawaddy River basin. Talismans imbued with magical properties are a feature of all belief systems.1 They are displayed openly and activated during rituals or kept secret, hidden from public gaze.

The talismans in the Zelnik István collection function specifically in a Myanmar belief system but also in a wider Southeast Asian context. The belief system encompasses Buddhism, spirit religion, astrology, cosmology and numerology and faith in the power of Nature and sacred objects. In general terms, the function of a talisman is to manage risk and immeasurable uncertainty by maximising good luck, minimising bad luck and in certain circumanstances, causing bad luck to an adversary.2 Malinowki viewed this behaviour as a type of ignorance “magic flourishes wherever man cannot control hazard by means of science”.3 The artisans who produced the talismans in this collection have been identified as Burmese and Tai (probably Shan and Khün), who used chiselling, dyeing, cutting and polishing techniques. Raw materials were selected for magical properties.

Gemstones heal and bring good luck; glass, a rare and desirable import is identified with alchemy-its early manufacture a closely guarded technological secret. Certain types of Southeast Asian woods, for example mai teng (Shorea obtuse) are considered auspicious. The petrified wooden talismans in this collection were sourced with this attribute in mind. A connection exists between these thousand year-old talismans and twentieth century magical practices. Elderly villagers who live in rural areas along the Thai-Myanmar border recall their fathers taking similar animal talismans into the forest when hunting.4 They remain popular with soldiers on active duty and men working in dangerous occupations such as construction. Today, forests are degraded or have been destroyed by over logging and although hunting wild animals is now illegal the animals that remain are under threat and some have already reached the point of extinction.

Animal talismans are therefore a legacy of an earlier period when their physical presence was a reality.

During the Pyu Era, the people of Myanmar were farmers settled in small communities. They practised irrigated agriculture and hunted in tropical forests full of wild animals that provided food, medicines and clothing. Hunters enhanced their skills by acquiring, through supernatural means, the physical and mental characteristics of the animals they pursued. This involved owning replicas of the wild animals they hunted and good luck charms made from the hair, bones, skin and teeth of those they captured and killed. However, all talismans were powerless until a spirit doctor (saya/hsaya: Burmese, sala: Shan) had charged them with magic. The process of empowerment involves chanting incantations and spells in the local language or in Pali, the language of Theravada Buddhism accompanied by special breathing exercises and cleansing rituals. Most objects in this collection are of a size to wear on a string as a necklace or keep in a shirt pocket or hidden in the folds of a turban.

Once empowered a talisman could be activated when danger threatened by holding it in the palm of the hand and massaging it while uttering the magic spell a hsaya had prescribed. This caused the animal represented by the talisman to magically appear. Talismans were strong deterrents when the animal that came to life possessed superior physical power to ward off other wild animals and human assailants. The talismans that function within this type of power are tigers, bulls, rhinos and bears. 5 There are 158 tigers, 1 rhino, 13 bulls and 3 bears in the collection, suggesting that tigers were the most popular talismans for this type of magic.

A hsaya can also create magic by transmitting desirable animal traits directly to the owner of a talisman. As well as physical strength there are other beneficial powers like cunning, agility, dexterity and raw intelligence. The magic spells that hsaya used to activate talismans were passed orally from one generation to the next, usually within hsaya families. Oral spells were later written down in mulberry paper manuscripts and on cotton. Items of this nature are also represented in this collection. There is no accurate date to confirm when written records began but mulberry paper and cotton have been in circulation for at least a thousand years. 6 These talismans represent animal power that can be transmitted and converted into human power. The same principle applies to animal tattoos. The tattooed person rubs the surface of skin over the tattoo and chants a magic spell. According to Chinese chronicles, the custom of tattooing developed in the early Pyu Era (circa 200BCE- 400 CE). Chinese accounts describe tattooed people living on their southern borders in present day Yunnan, Laos, northern Thailand and Myanmar.

The tiger talismans in this collection are made from a range of gemstones, including carnelian that is painted with white stripes, probably a way of enhancing magic power (Br1354, 847, 1053, 1055, 1714).

The collection also contains a tiger’s tooth coated in silver and bound with tiger hair (Br1032), a set of genitalia from a tiger and an inscribed tiger bone worn as an amulet (Br2262, 2263). These objects symbolise supernatural strength, speed, stealth and fearlessness. Although associated with men engaged in risky activities, tiger talismans also feature in the lives of those engaged in other occupations. Politicians, musicians, dancers and actors required the physical strength of tigers to sustain them through long sessions of public performance.

Students sought power to help them stay alert during extensive periods of study for examinations. In terms of administering tiger power, hsaya were aware of negative power that could be accidentally unleashed. They wrote cautionary notes in their mulberry paper manuscripts warning that tiger power needed careful handling because it could spiral out of control with disastrous consequences. Young men were considered particularly susceptible and blamed for drunken, aggressive and reckless behaviour while under the influence of tiger magic. To neutralise negative outcomes of this intensity required special rituals performed by a high-ranking Buddhist monk or senior lay hsaya.

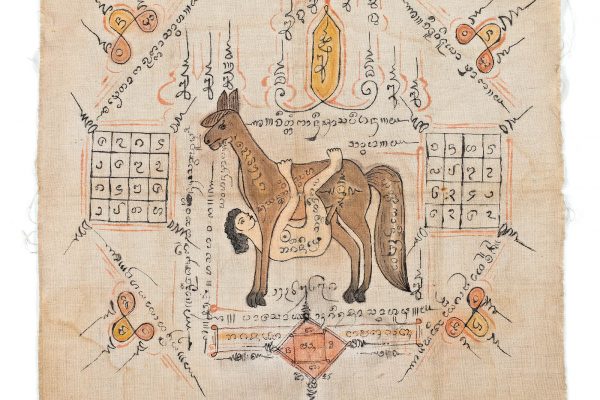

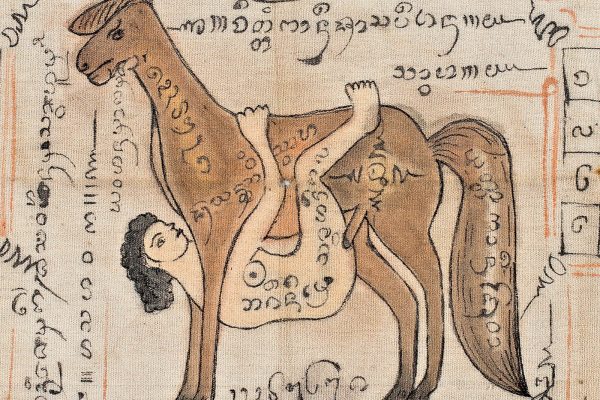

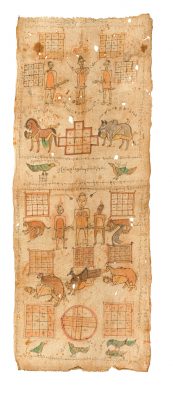

In this collection there are 13 gemstone talismans classified as bulls and an illustration on cotton. A bull has the desirable attributes of physical strength matched with a volatile temperament (Br1110, 1590, 1124). The cotton hanging in the collection shows a bull passing strength through semen to a woman during sexual intercourse.

The bullish attribute of unpredictable behaviourfrightens other animals and terrifies evil spirits. A contemporary version of the bull talisman is employed by hsaya in the Shan States who draw the image on a sheet of mulberry paper, fold it with a specified lucky number of folds and set the paper alight while incantations are offered to drive away evil spirits. The ash is collected and either diluted in water to be taken as a drink or mixed with oil and rubbed into the skin. Both remedies reinforce the power to expel evil spirits. Bear talismans in this collection represent physical strength with the added feature of sharp flesh-tearing claws that frighten wild animals and human assailants. In contrast, monkey talismans (Br1118) are valued for speed, cunning, agility, intelligence and dexterity, attributes useful to soldiers on active duty and criminals evading capture.

By adding extra spells a hsaya can prevent pursuers from inflicting injury from bullets, swords, daggers and knives.

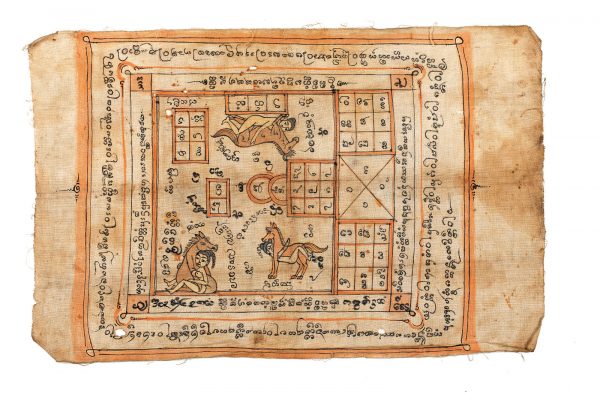

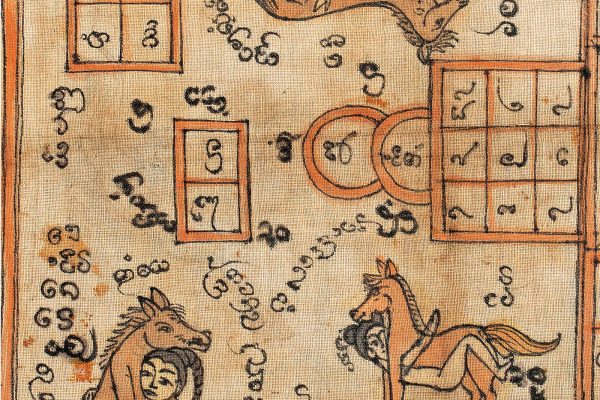

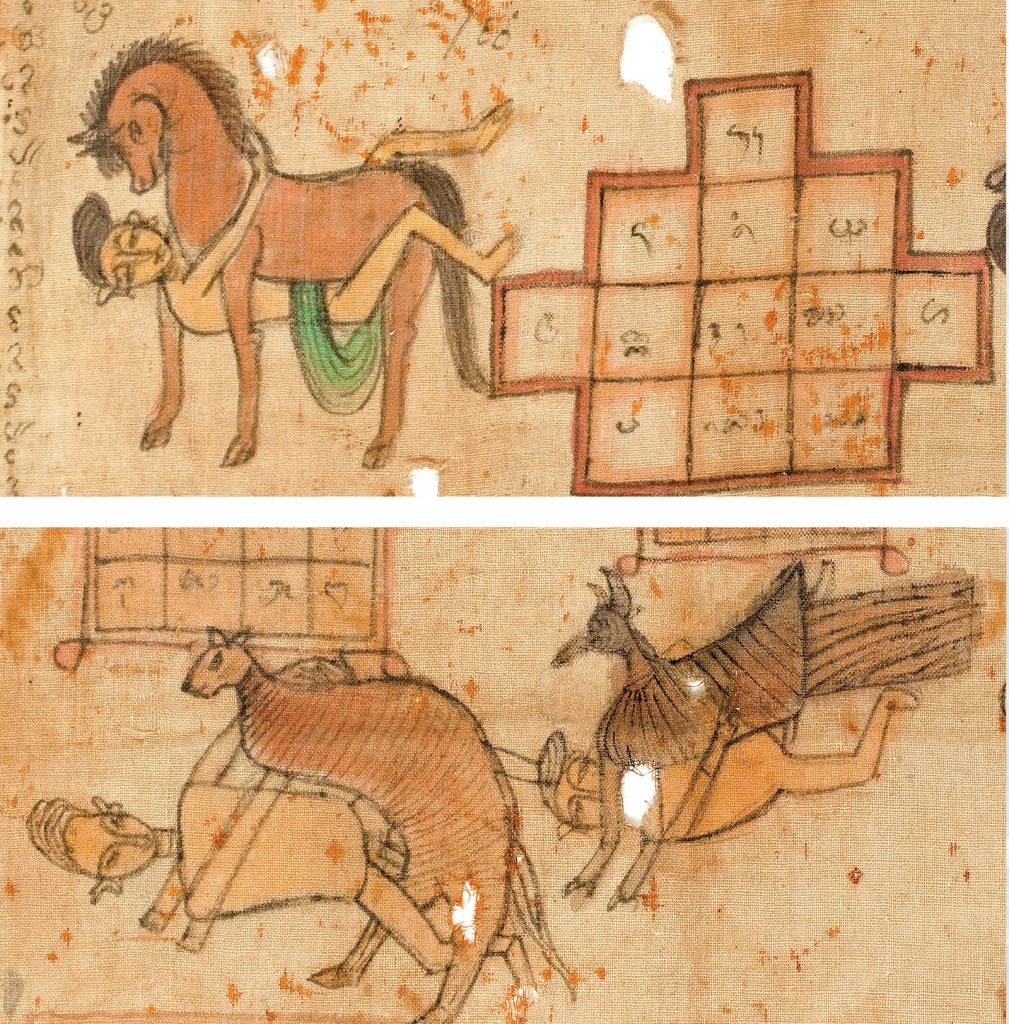

The glass and amethyst horses in this collection represent Buddhist and animist beliefs (Br739, 1108). A horse symbolises love and fidelity, as characterised by Kanthaka the faithful horse of Prince Siddhartha who died of sorrow when the prince left the palace to follow the path to Enlightenment. A male horse can also symbolise karma a condition defined by the Buddha as intention in physical, vocal and mental actions that lead to future consequences in rebirth. The horse in this case represents the rebirth of a loving husband who dies and his karma leads him to be reborn as a horse. His wife recognises him in this rebirth and they continue in the loving relationship of his previous life as her husband. Illustrated examples of this story form part of the collection, reproduced on mulberry paper and cotton. They show a woman clinging tightly to the underbelly of a horse while having sexual intercourse (Br2173). The sexual act between horse and woman is defined here by the Pali word me a (universal loving kindness). Illustrated talismans of this type often have a Pali text encircling the image that includes the words mea piyam ma ma (loving kindness to me). The sexual act itself conforms to the concept of karma, although intercourse between an animal and a woman is also defined as saiyasart, meaning a less austere interpretation of Buddhist teaching applies. In animist terms, the power of semen passes to women to give them supernatural physical and mental strength. The cotton hanging in the collection has separate images of a woman having intercourse with a horse, bull and garuda and with an unidentified striped animal (Br2175). There are illustrations of small animals one shows a rat sucking the penis of a tiger. Local astrological charts place the rat and tiger opposite each other as rival forces so the act of suckling demonstrates me a in terms of the strong helping the weak and symbolises reconciliation between enemies.

The horse in this case represents the rebirth of a loving husband who dies and his karma leads him to be reborn as a horse. His wife recognises him in this rebirth and they continue in the loving relationship of his previous life as her husband. Illustrated examples of this story form part of the collection, reproduced on mulberry paper and cotton. They show a woman clinging tightly to the underbelly of a horse while having sexual intercourse (Br2173). The sexual act between horse and woman is defined here by the Pali word me a (universal loving kindness). Illustrated talismans of this type often have a Pali text encircling the image that includes the words mea piyam ma ma (loving kindness to me). The sexual act itself conforms to the concept of karma, although intercourse between an animal and a woman is also defined as saiyasart, meaning a less austere interpretation of Buddhist teaching applies. In animist terms, the power of semen passes to women to give them supernatural physical and mental strength. The cotton hanging in the collection has separate images of a woman having intercourse with a horse, bull and garuda and with an unidentifi edstriped animal (Br2175). There are illustrations of small animals one shows a rat sucking the penis of a tiger. Local astrological charts place the rat and tiger opposite each other as rival forces so the act of suckling demonstrates me a in terms of the strong helping the weak and symbolises reconciliation between enemies.

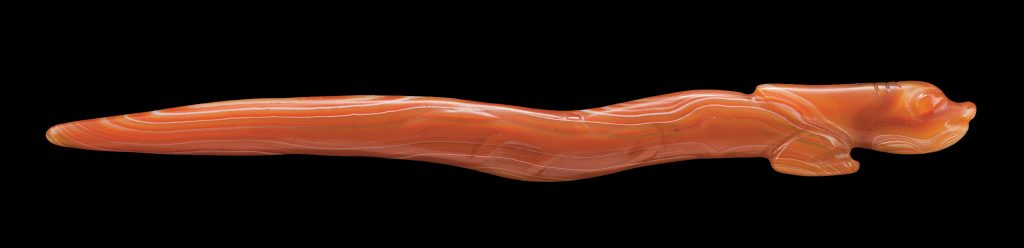

The agate lizard in this collection is a symbol of good luck and prosperity (Br1370). Lizards (I cawk/zeung heun) are welcome in domestic dwellings, identified by their loud and distinctive call that is considered auspicious. The sound is interpreted in local languages and chanted in magic spells. Lizard talismans were valued by traders who before the advent of modern roads, travelled overland on hazardous journeys with laden pack animals, crossing narrow mountain passes and malaria-infested forests where they were subject to disease and attack by bandits.

On occasions when their caravans were raided and they were left destitute, the lizard talisman ensured the kindness of strangers who came to their assistance. If a trader sensed danger and needed help he held the lizard talisman in his hand and offered incantations for protection, good luck and support in adversity. Lizard body tattoos and lizard talismans drawn on mulberry paper or cotton are another form of this talisman and are activated in a similar way. Some of the gemstone animals feature in Theravada Buddhist and Hindu cosmology.

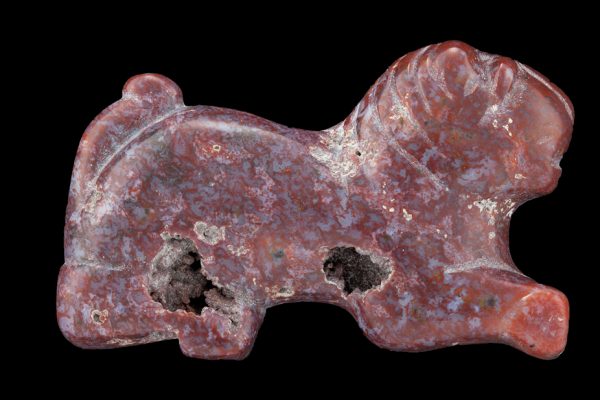

The lion represents the mythical king of beasts (rachasee/singha) who lives in the Himaphan (Himmavanta) forest that surrounds the base of sacred mount Meru. He is a symbol of power and protection (Br1125, 1061).

The elephants in the collection have celestial status as descendants of the god Brahma who confers wisdom, as envoys of Siva who bestows power and wealth, as representatives of Agni who symbolises the cleansing power of fire and as agents of Vaisya symbol of love, compassion and success (Br978, 1890). The 36 white elephants in the collection specifically denote royalty and symbolise victory (Br1120). In physical and mental terms, elephants represent strength, tenacity and intelligence.

The birds in this collection include owls, geese and crows. The owl is an augur of bad luck, particularly when it flies into a house because evil spirits will follow (Br1115). The spirits are appeased with selected offerings placed on a tray. They include an owl talisman and candles, flowers and food.

The tray is situated at the exact location where the owl entered the house. A hsaya and members of the household offer incantations when the offering tray is in place.

A goose (hintha or hamsa) is a semi-divine bird whose power lies in carrying messages between heaven and earth (Br1009). Crows give power to humans and can also transform them (Br1681). At the time of the founding of the Myanmar kingdom and its principalities a band of crows chose a cowherd to be the prince of a Shan state. They collected him from his humble dwelling and transported him through the air in a basket to be set down in a palace prepared for him. As time passed the prince angered the crows with his ingratitude and failure to acknowledge their role in making him ruler. As a form of punishment, the crows kidnapped the prince and flew with him to a clearing on the edge of a forest where they abandoned him in isolation. He was then transformed into a guardian spirit of the principality he had ruled.

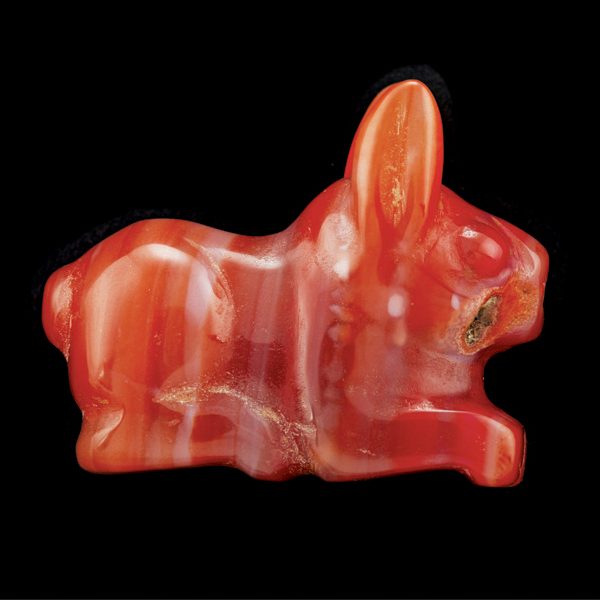

Talismans assist our understanding of astrology within the Myanmar belief system and in particular how planets and stars function in the solar system. The peacock talisman represents the sun, giver of life (Br758). It travels across the sky and around Mount Meru pulled along in a horse-drawn chariot. As avatar of the sun, the peacock is symbol of Myanmar kingship, reflected in the titles of “Lord of Life” and “Lord of the Sky”. 7 A peacock talisman provides protection during daylight hours. The moon is symbolised as a hare/rabbit that is also pulled across the sky and around Mount Meru in a horse-drawn chariot (Br1673, 2235). Because it is easily visible from earth and its appearance changes every day as it waxes and wanes, the moon has long been a practical tool for calculating auspicious and inauspicious periods of time. Full moon is most auspicious and owning a talisman representing the moon ensures benefits during the lunar cycle.

The sun and moon are subject to eclipses, inauspicious periods of time caused by the god Rahu who swallows them in his large mouth. Light and life are restored when he is forced to spit them out again through the force of incantations appealing to the superior power of the Buddha. Burmese and Shan talismans represent Rahu as a head and face with arms and no body or more unusually, in the form of a frog. There are 10 gemstone frogs in this collection. As a harbinger of monsoon rain, the frog represents the forces of nature and through its association with rain is a fertility symbol (Br1601, 1010). The role is affirmed in Burmese, Shan and Khün texts written in mulberry paper manuscripts and on cotton talismans. Texts give instructions on how to fashion an image of Rahu as a frog holding the moon in his mouth. 8 They contain appeals to Rahu to protect the daylight hours and guard the night, a role shared with peacock and rabbit talismans. 9

Certain animals present in this collection are associated with the Shan and Mon eight time period cycle and the Chinese twelveyear cycle. There is evidence of both counting systems in Myanmar although they are subject to local interpretation, particularly Shan and Mon astrological charts in terms of choice of animal and the way they are depicted.10

The elephant (Br1946) tiger (Br2000) garuda (Br2248) lion (singha) (Br1126) rat (Br1116) monkey (Br1592) and ox/bull (Br772) rabbit/hare (Br1672) horse (Br1652) cockerel (Br2256) are represented here. Interestingly the pig and naga are missing from this collection.11

Coordinated with the twelve animals are designated planets, gods and goddesses, plants and cardinal and sub cardinal directions. The year of birth influences one’s physical attributes, personality, talents and behaviour and is a significant tool in fortune telling. For example, a monkey talisman indicates a person born in year nine of the twelve-year cycle under the influence of the moon. He/she is likely to be an extrovert, a philosopher and talk intelligently so that people listen. The planet Mercury is in the heart, making the person steady and understanding in nature. Mars and Mercury are in the hands so they work slowly. Venus and the Sun are in the feet so walking is disliked. Saturn dominates the lower body making the person passionate and full of sex appeal.

The other counting system used extensively in Myanmar divination involves the time of birth calculated from eight time periods. They are Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday morning and Wednesday afternoon Thursday, Friday and Saturday and matched in sequence to the Sun, Moon, Mars, Mercury, Rahu, Jupiter, Venus and Saturn and to eight animals, the cardinal and sub cardinal directions and to numbers that relate to units of energy (life force). Add life force numbers. Four animals are constant, the garuda, tiger, elephant and naga/dragon. Other animals vary according to local custom and are chosen from a male elephant or female elephant, cow, guinea pig, rat or goat. A divination diagram features eight animals placed in separate segments of an octagon. Certain animals are opposite each other to create balance. A naga/dragon, representing Saturn, the southwest, lead and Saturday is always opposite a garuda, symbolising the sun, the northeast, gold and Sunday because they are sworn enemies. A singha is usually opposite an elephant.12 To establish whether a person is in an auspicious or inauspicious time in life involves a calculation that begins with the animal representing the time period of birth.

The hsaya adds up the numbers relating to life force counting clockwise for men and anticlockwise for women until he reaches a number that coincides with the person’s age. If the animal (and by association planet, metal and cardinal direction) where the counting starts is in harmony with the animal where the counting stops then the person is in an auspicious period. If the animals are opposing forces, it is inauspicious.

In conclusion, the animal talismans in the István Zelnik collection are historically significant in terms of raw materials and craftsmanship. They are meaningful symbols of a belief system practiced during the Pyu Era that was later recorded in texts and illustrations depicted in manuscripts and textiles, also represented in this collection. In total, the collection demonstrates an historical progression from oral communication to writing and illustrations of supernatural beliefs and practices.

Note

1. Small clay animal figures used to generate supernatural power are traced to the transitional Bronze and Iron Age, 900-600BCE (Higham and Thosarat 1998). Terence Tan: The Journey through Beads from Prehistory to the Pyu States in Myanmar.2. Knight, 1921, quoted at the ANRC and RCSD workshop, Chiang Mai 15-17 January 2010.

3. Malinowski, B. Sex Culture and Myth, New York 1962, p. 261.

4. Conway, Susan Tai Magic: Arts of the Supernatural (Bangkok 2014).

5. I have not found references or experienced personally the use of rhino talismans. However, powdered rhino horn is a well-known aphrodisiac.

6. The craft of paper making probably came from China circa 10th century CE.

7. Conway, Susan The Shan: Culture, Arts and Cras (Bangkok 2006).

8. Saimong Mangrai (1981 pp. 194-195) quoted in Conway, S. (Bangkok 2014).

9. Rahu as a frog appears on talismanic shirts (Conway Tai Magic: Arts of the Supernatural, 2014).

10. Conway, Susan Tai Magic: Arts of the Supernatural (Bangkok 2014, pp136-139).

11. This is true of some other collections in Southeast Asia.

12: Sirot Chutiwat described this placement as opposition forces being neutralised (oral communication, Hang Dong, March 2013).