Volume 1, Issue 3, July-August 2020.

The ‘First’ Research-based Artworks in Cambodia

Dr. Caroline Ha Thuc

The question of who the first artists were to engage in research-based art practices in Cambodia revives the debate about which contemporary artwork was the first to be produced in the country; which is a moot point in any case, since there is no clear definition of what contemporary art actually is. In Cambodia, the concept of contemporary art remains an “amorphous conception” and Pamela Corey showed how three distinct artists, Leang Seckon, Vann Nath and Sopheap Pich, can all claim to be “the first Cambodian contemporary artist”. 1 With regard to research-based artists, the question becomes even more difficult since what a researchbased artwork is cannot be neatly defined either. These practices could be broadly described as artistic endeavors grounded in a research process that is based on the methodologies of work and on the languages of historians or of social scientists in general, the outcome of which is then displayed as or transformed into an artwork.

In Cambodia, such exercises are very recent, and their emergence follows the development of contemporary practices that have opened up the field of art and allowed cross-disciplinary dialogue, as well as permitting original methodologies of work to arise. In light of the specific country context—decades of colonization, 2 the Khmer Rouge period, 3 and today’s authoritarian regime with, notably, state-controlled media and a weak education system—these practices have mainly originated in a desire among artists for emancipation and in their eagerness to learn, produce and transmit knowledge. Their emergence has also coincided with a revival in photographic art, 4 in particular with the establishment of two important festivals, the Angkor Photo Festival and Photo Phnom Penh, 5 which have encouraged artists to engage in investigative fieldwork in their surroundings and document reality from a Cambodian point of view. Research-based art practices evolve over time because their research component tends to be elaborate and diverse. However, and even though the dates and selection of artists can be debated, Messengers (2000) by Ly Daravuth and the Bomb Pond series (2009) by Vandy Rattana offer two useful benchmarks and points of departure in understanding the development of such practices in the country, and the evolution of their form.

From the end of the 19th century onwards, realist art forms opened the path to the possible combination of art and documentation, connecting today’s research-based art practices with a longer tradition of art rooted in reality and fieldwork. In Cambodia, the practice of documenting reality and engaging in fieldwork might have its roots in the postindependence years. Until the beginning of the 20th century, there were practically no full-time artists living in the country: most of the artists who decorated the temples were farmers who would only work as artists on an ad hoc basis. There was only a small group of full-time artists who worked within the Royal Palace in the Royal Palace Workshop, who were dedicated to making objects for royalty, and to decoration.6 In 1917, George Groslier transformed this Workshop into the School of Cambodian Arts but, as Corey recalls, art students were trained to remain confined in their studio.7 In contrast to what happened in Vietnam at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Hanoi, modern art was not encouraged. However, when Vann Molyvann8 became the first rector of the University of Fine Arts in 1965, he established a research institute focusing on the study of traditional arts and techniques.9 Research was strongly promoted during these first post-independence decades with a national drive to preserve traditional heritage and to rebuild national identity after almost a century of colonialism. Against Western epistemologies, Cambodian modernism searched for its own roots and modes of knowledge production. Some artists were sent to the countryside to visit the hill tribes in order to collect and learn traditional dances, music, and certain arts and crafts that were threatened with extinction, mural painting, and traditional stories or legends. Most of these research materials and paintings from that time were lost during the Khmer Rouge era,10 but it is worth noting that a few painters, for example Sam Yuan, harboured “a desire to reflect contemporary social issues and to incorporate these elements into painting”.11 Perhaps, what is left from this heritage is a taste for ethnographic fieldwork research, which today dominates Cambodian researchbased art practices.

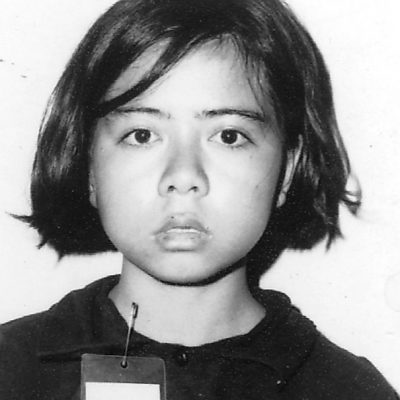

As mentioned above, Messengers (2000) by Ly Daravuth may well have been the first research-based Cambodian artwork. The installation is composed of some thirty black and white photographs representing portraits of young boys and girls, slightly blurry and formatted as ‘mugshots’ with numbering at the bottom. For most viewers, they are read automatically as portraits of the victims of the Khmer Rouge Regime and, in particular, victims of the S-21 prison in Phnom Penh. This former school is sadly notorious for the killing of about 14,000 Cambodians who were all first photographed in the same and now notorious way. In 1980, S-21 was transformed into The Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, which displays the portraits of some former inmates, initially with the intention of allowing people to identify relatives and then, more confusedly and controversially, for anyone wishing to comemorate, or for tourists.12 Despite this first and instinctive reading of the work, Messengers does not actually include any portraits of victims. Ly Daravuth conducted research at the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam)13 and selected 24 portraits of children who worked as messengers for the Pol Pot Regime. In order to call for a renewed perception of the images, he took 6 portraits of present-day children, that he then edited in such a way that the images resemble the original portraits. In the background, Khmer Rouge songs are played.14 Messengers does not actually involve much research, but the critical way in which the artist questions, archives and processes documentation is crucial for the future research engagement of artists in the country.

Exhibited internationally as early as 1997, and widely reproduced, the S-21 mug shots have quickly become “the icon of the Cambodian Genocide” and broadly of the Khmer Rouge, without people really delving deeper into what it is they reflect on.15 Messengers thus challenges our preconceived views on archives when history and remembrance have become automatized and overly mediatized. The installation featured in a group exhibition entitled The Legacy of Absence: A Cambodian Story, curated by the artist and Ingrid Muan. Together, they are the founders of the Reyum Institute where the exhibition took place in Phnom Penh. In 2000, the question of public memory in Cambodia was a burning issue, especially with some pressure from NGOs and foreign curatorial teams, which commissioned works dealing with the traumatic experience of the Khmer Rouge. The chosen priorities were restoring and healing society, as well as reviving traditional arts, in a way described as too invasive by Pamela Corey and often criticized by the artists themselves, who felt pushed towards a topic they needed more time to apprehend.16 Messengers functions as a warning about the way the omnipresence of the genocide tends to frame Cambodian identity. Ashley Thompson aptly remarks that the DC-Cam where all the archives and photographs are kept and recorded is not known as the Documentation Center of the Cambodian Genocide but as the Documentation Center of Cambodia, favouring a direct association between Cambodian identity and the genocide. Furthermore, she notes that the magazine they publish is entitled Searching for the Truth, “linking the search for truth to any documentation process dealing with the Khmer Rouge”.17 With Messengers, Ly deeply questions another preconceived reading which consists of associating automatically and superficially archives and truth, whatever the context may be. For Thompson, the work “attempts to problematize the assimilation of document and truth aimed at countering an increasingly dominant discourse that tended to reduce the complexity of both terms”.18 The installation is an invitation to open up to a plurality of truths and to critical reading, despite its research component or its use of archives.

Ly is better known as the founder of the Reyum Institute, and as a curator, writer and lecturer of art history than as an artist, and he did not continue to produce artwork. Somehow, his work remains isolated despite other Cambodian photographers using his ‘mugshots’ as a departure point for their work. Heng Sinith, for instance, collaborated with researchers from the DC-Cam in order to rediscover some cadres and to photograph them again in their daily life, as fathers or villagers.19 Like him, Khvay Samnang used the S-21 format to portray 800 high school students for their graduation in one of his earliest series, Reminder (2008), creating a disturbing tension between a traumatic past and the future of these young adults. Yet, none of these works have the critical power and complexity of Ly’s.

For Vandy Rattana, “doing research can be an empty phrase if it is not done with critical thinking”20 and the artist is the first person in Cambodia to combine Ly Daravuth’s critical approach with on-site investigations, definitively opening the path towards the development of research-based art practices in Cambodia.

Rattana’s Bomb Pond series (2009) was exhibited at dOCUMENTA (13) and is a series of photographs focusing on the American bombing of Cambodia during the Vietnam War. A self-taught photographer, Rattana began by documenting the daily life around him. Looking Inside (2005) is a series of portraits of his neighbours and Looking in my Office (2006) documents his work as a telephone technician at his office.21 Later, with Walking Through (2008), he visited some rubber plantations to explore the landscapes, which was when he discovered the bomb ponds. According to him, Bomb Pond marks a turning point: when he saw that first crater, he started to question himself about history and discovered his ignorance: [previously], “I was stupid and did not think for myself”.22 Eager to learn about these ponds, he did some research and found a map of the bomb sites in a Canadian magazine, which ultimately, he was unable to use. He preferred to rent a car and drive to the border where he systematically asked local people about those ponds. Usually, people knew and took him to them. They would also tell him a lot about their memories of the war. Rattana denounces the systematic attempt by the government to eliminate traces of the past, and a system that discourages genuine research and critical thinking. For him, research is a response to this ignorance, and he often cites Vandy Kaonn’s book Cambodia or Politics without the Cambodian to emphasize the lack of political agency of the Cambodian people within their own country.23 Research here was thus mostly done in the form of fieldwork and it opened up new perspectives for the artist who began to critically question everything around him.

Earlier, in 2007, following a photography workshop organized by Stephane Janin, Rattana co-founded the artists’ collective Stiev Selapak with a group of artists including Khvay Samnang, Lim Sokchanlina and Vuth Lyno who are still working for what has become the independent art space Sa Sa Art Projects. Rattana had an important influence on the group and more generally on the local art scene. According to Vuth Lyno, “documentary photography and capturing local reality were critical in our practice from the start, inspired by Vandy whose passion was to create visual archives of present-day Cambodia”.24 Zhuang Wubin also underscores his influence on the process of work of other Cambodian artists: “due to his sense of mission in relation to Cambodian photography, Vandy has become the rallying point for the likes of Khvay Samnang, Heng Ravuth and Lim Sokchanlina, who emerged slightly later.”25 Rattana, though, felt and still feels isolated, and he left the group shortly after to pursue his career mainly outside of Cambodia. Nevertheless, both Sokchanlina and Khvay, along with an increasing number of Cambodian artists, are today deeply engaged in research-based art practices. Just like Rattana, they use research as a way to emancipate themselves from history and from the current authoritative regime, and in order to regain agency as local artists.