Volume 2, Issue 1, January-February 2021.

The Journey

through Beads from Prehistory to the Pyu States in Myanmar

by Terence Tan

From the Transition Period (The Bronze-Iron Age – circa 700 BC-200 BC) to the Iron Age (circa 400 BC-200 AD)

INTRODUCTION

The transition period in which the Bronze Age shifted to the Iron Age is most commonly referred to in Archaeology as the Bronze-Iron Transition Age (900 BC to 200 AD).

In the later part of the Bronze Age, people travelled further, explored new regions, and made new discoveries. It is a common belief among historians that travellers and traders from Greece, Rome, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, Central Asia, India, China and East Asia travelled to the Southeast Asian countries via land and sea routes. At that time, people in what is today’s Myanmar were still in the Bronze Age.

By coming into contact with these travellers and traders the local people must have adopted new technology and applied the new-found knowledge to their own work. It could be said that the Bronze-Iron culture commenced with its focus on glassmaking, alchemy and bead etching. One of the most significant discoveries was of mineral mines and semi-precious stones. Laboratory analysis has been performed on some of the remnants found and the materials were identified as carnelian, chrysophrase, chalcedony, agate, quartz, silicified wood and glass.

The Bronze-Iron Transition Period is a remarkable phase in the history of arts and crafts in that it is a period in which a great number of significant developments were made. These include: use of semi-precious stones, etching, bleaching and dyeing, distinctive bead designs such as the line-decorated beads, the carving of figurines, and the bronze iron (bi-metallic) combination in tools. This can be seen, for example, in swords with bronze handles and iron blades. Therefore, it could be said that technological change was at its peak in this period. In the later part of the Bronze-Iron Transition period, people started using gold in the form of nuggets, beads, jewellery and gold teeth. This is the period which could be termed the Iron Age or Pre-Pyu period.

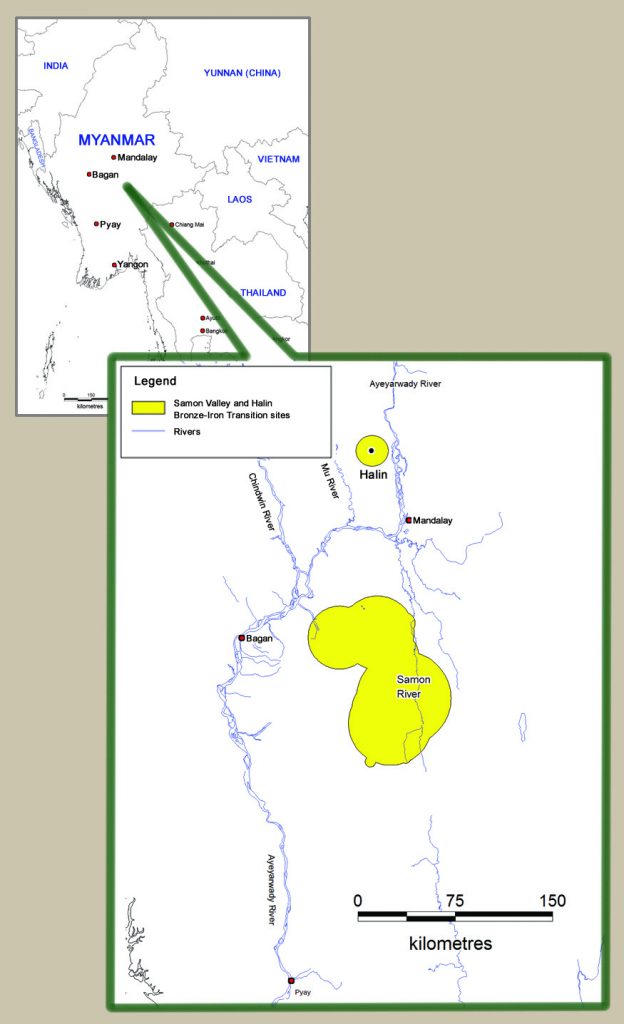

Map and Location

The most important Bronze-Iron site in Upper Myanmar is Halin because evidence from excavation sites show that it has been continuously settled from as early as the Bronze Age to the present day. Its importance is signified by the salt deposit on which the inhabitants depend on for trade and livelihood.

The most prominent and significant region in Central Myanmar is the Samon Valley since the majority of the excavation sites are found in that area. Geographically, its location turns out to be the gateway to Southeast Asia. Salt deposits and mineral mines in the area also helped the Samon Valley to advance in trade and culture. Bronze-Iron sites were scattered from Halin to Pyinmana, but the principal concentration was based in the Samon Valley. It is an area around present-day Pyawbwe, Yamethin and Tharzi along the Samon River which flows northwards into the Myit Nge River, which in turn runs into the Ayeyarwaddy. Most of pre-Pyu Culture flourished around the Samon Valley in central Myanmar so that U Win Maung (Tanpawaddy) and U Maung Maung Tin coined the term ‘Samon Culture’.

Burial Customs

Many kinds of burial customs have been observed at the sites of this period.

- Multi-layer burial

- Burial on potsherd flooring

- Two big earthen pots facing each other, encasing the corpse

- Bronze funeral embellishments of newer designs

- Unique procedures for burials noted in the endeavours of the people to preserve the corpses where they cover the whole body with a paste of slake lime and turmeric or a mixture of mastic and slake lime.

- Burial orientation observed to be headed towards the East and the North. In rare cases, Southward orientation could also be found.

Material Culture

Many kinds of burial customs have been observed at the sites of this period.

- Pottery

- Stone Culture

- Bronze Culture

- Glass Culture

- Bead Culture

- Introduction to Gold Culture

- Pottery

Pottery in this period is truly unique in terms of design and occurrence. No other prehistoric site in Southeast Asia yields such a variety of types and designs as those of the Samon Valley:

– A peculiar vast-shaped pot with four coin-sized holders attached to the short vase body was found among the finds. However, both the aim of the design and its function are obscure.

– An unusual type of liquid container is noted to have emerged in this period: a variety of cylindrical pot with small holes near the top, believed to be one of the most outstanding features among the pottery finds.

– Three legged cauldrons, which were used to brew liquor, indicate that people of this period had knowledge of brewing technology and were in the habit of using alcoholic drinks from as early as that time.

– Small cups, bowls, plates and containers of various shapes and sizes can also be regarded as typical features of prehistoric pottery wares of the period.

With regard to pottery, it is assumed that there were different techniques for different items that would suit the functions, the life-style and the needs of the society of that era.

Stone Culture (Rings & Bangles)

Disc-shaped bangles are believed to have been popular from the late Stone Age and throughout the Bronze Age. They reached a peak in popularity in the Bronze-Iron Transition Period. Bangles vary not only in shape but also in size from small to very large. Technologies from the Bronze Age such as grinding, filing and polishing were used to produce pear-shaped, circular, triangular, sub-triangular, round with collars and rectangular designs. When technology improved, polished collared stone bangles (T-Zone shape) emerged. There are also some distinct innovative designs such as spiked bangles and mega-bangles which are very rare.

When new ornaments like glass and metal bangles came into the picture, stone bangles became less common. However, people still wear bangles made of jade or other semiprecious stone to this day, particularly Chinese people who wear jade bangles as charms for longevity and for protection.

Bronze Culture

In the Bronze-Iron Transition period, the application of fire and heating made significant advancements possible in general technology, including ornamental arts and crafts. People were able to melt metals to make weapons, utensils and ornaments, etc. Bronze Age people were able to cast metal and forge alloys and their technology improved over time.

When observations are made of bronze artefacts from the Bronze-Iron Transition Period:

a) bronze implements, b) utensils, c) bronze figurines d) bronze ornaments, and e) other artefacts come onto the scene.

a) Through advanced heating application technology, bi-metallic weapons were produced in the Transition Period. The use of bi-metallic technology (bronze-iron) is most commonly found in the production of swords and their handles. This can be seen, for example, in swords with bronze handles and iron blades. The use of ivory provides an image of their elite society. Some bronze artefacts show the influence of Greek culture. In some cases artefacts still have prehistoric textiles adhering. The Samon Valley bronze artefacts share features with of those from Dian Culture, southwest China, specifically from Shizhaishan and Lijiashan. Thus traces of the influence of Dian culture can be detected in the bronze culture of the Samon Valley.

b) Gourd-shaped liquid containers or water bottles and a few cups were found at the Myauk Mee Gone site. Bronze plates and spoons were found not only at Myauk Mee Gone but at other Bronze-Iron Transition sites as well.

c) Bronze figurines of a mountain goat with a single horn (probably an icon with a specific significance in the local culture), an elephant and a horse were also discovered at Myauk Mee Gone. One unusual find from the same site is the figurine of a human being offering a boat to a mythical creature (half man, half bird). This find is one-of-a-kind and it is thought to be related to the Dian Culture, but the actual interpretation is lost with its creators. The earliest human image cast in bronze, a figurine of a female deity, was found at the Pyawbwe site. This particular image is the first figurine of a human being cast in bronze in the history of bronze culture in Myanmar.

d) There seems to be a continuity of human belief in ornament throughout history. Bronze bangles and anklets, differing somewhat from the stone bangles came into use. They are mostly hollow and rounded. One spiked bronze bangle has been found at the Halin site. It is a modification of the spiked stone rings and is believed to be the only one found in Myanmar so far. Some finds reveal a very peculiar trend of fashion regarding ornament. In one particular find, bronze wire is coiled around a skeletal hand and in another case there seems to be a continuity of rings joined or connected which resemble a coil. The same concept is used on fingers as well but whether they are used for fashion style or as hand or finger guards is uncertain. Both men and women wore ear ornaments in that era; however, the difference between the ear ornaments of those days and the contemporary style lies in the size of the hole that accommodated the hangers of the pieces. In ancient times, people made holes big enough to pass one’s fingers through. Therefore, the hooks as well as the ear pieces were very heavy and thick. Such elaborate designs, which would not be found today, were uncovered at the Pyawbwe site in Samon Valley.

e) Among the finds from the Bronze-Iron Transition burial sites are some Kyei Dokes and coffin decorations. Kyei Dokes are small packets or bunches of bronze wires which are most commonly used as decorations to represent currency wealth. The concept of Kyei Doke is believed to have derived from the hay stacks where farmers store their wealth in heaps or piles of hay. From the earliest ages to date, the inhabitants of Myanmar believe in life after death. People try to portray their beliefs about the next life through these symbols. The coffin decorations and the symbols are assumed to be dedicated to the Mother Goddess who represents fertility.

Glass Culture

Glass ornaments from this period shed light on the profile of ornamental arts and crafts of the era. Glassware is produced by applying advanced heating technology, and the use of silica compounds came into the picture in the Bronze-Iron Transition period as a new technology.

However, only a few colours were found to have been used in the Samon Valley and Halin whereas many more variations in colour were used at the sites further south. Observations of the products indicate that the most popular colours for glass in the Samon Valley and Halin area in those days were blue, green, blue-green, and purple. It could be that the colouring elements accessible to the Samon area were limited or it could have been a deliberate fashion choice by the people of the area. Evidence of glassmaking is also found in the Near East and in India. The blue glass bangles that are found in Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia appear in the Samon Valley and at Halin. They suggest a regional trade in high value status objects. It is not yet clear whether glass was imported as a raw material and the rings, bangles, beads, and discs were designed and produced locally, or the raw material was procured locally. However, the latter would be the most feasible hypothesis because of the quantity found in the Samon Valley, which is much greater than that of other regions.

Glass ornaments are not found at all pre-historic sites in Myanmar. The glass ornaments have been found exclusively in the Samon and Halin regions to date. Even in the Samon Valley, not all sites have yielded ornaments. Findings include: a) glass rings, b) glass bangles, c) glass beads, and d) ear ornaments.

a) Glass rings are typical finds on prehistoric burial sites, Evidence of the fact that tradition or customs of the preceding periods still had influence on the people of the new age could be seen at the burial sites. Those rings are one of the most significant innovations of the period. Some rings are found in situ, attached to bones. The rings are thought to have been worn not only for adornment but in association with traditional beliefs and ritual procedures. The rings imply possible associations with the Chinese ‘Pi’ discs and the ‘Yin and Yang’ concept.

The Chinese culture of the Western Zhou Dynasty (11th – 8th Century BC) is assumed to have spread to Samon Valley when the Chinese fled from their kingdom at the fall of their dynasty. Although Chinese culture could have been adopted by the local inhabitants at first, it is most probable that the customs, modified and merged with existing culture, had synthesized into an aspect of the local culture later.

Glass rings from this period resemble the stone rings found on skeletons of earlier eras. The shape of the rings is mostly flat and round with only one ring in oval so far. The sizes of the rings vary from 1 to 13 inches in diameter, but most rings are between 4 and 8 inches. Rings from one to two inch diameter are mostly purple and green discs. They would have been used as beads or for decorative purposes because they are too small to be worn on the hand. Bigger rings with a diameter of 3 to 13 inches are mostly blue, green and blue-green, and are believed to have been worn by the elite, the rich and by influential people since they are rare, especially the mega-rings which would have a diameter of 13 inches.

b) Glass bangles are mostly found among the finds of Halin, as well as at the Myo Hla, Aye Thar Yar, Tamar Gone, Thein Te, Leh Way, Pei Gone and Myauk Mee Gone sites in the Samon Valley. Broken pieces as well as whole bangles have been found. The finds are mostly of blue, green, and blue-green colours. They are plain in design, similar to the modern bangles, and therefore could be a prototype of today’s version.

c) Glass beads of different size, shape and design such as figurines, claws, teardrops, leaves, bell, cylindrical, oblong, polyhedral, and cornerless cubes are yields of the sites mentioned above. They are either colourless, blue, green, blue-green, or purple. Those plain glass beads of different sizes were found in the Samon Valley area only and not at the sites of southern Myanmar. Consequently, it can be assumed that the Samon Valley region was once the manufacturing site for blue and green beads. Multi-coloured micro glass beads were found in abundance in all shapes at all the Bronze-Iron Transition period sites. Multi-coloured micro glass beads are assumed to have been used for decorative designs on clothes and other ornaments. The use of micro glass beads for decorative purpose is obvious and it is a common feature of all sites. However, the custom or tradition of how and where they were used would most probably be different due to their cultures and the ecological features of the respective sites.

d) Ear ornaments in the shape of the crescent moon were sometimes unearthed from the abovementioned pre-historic sites in Halin and the Samon Valley.

Glass rings—Glass bangles of the Prehistoric Era were used as ornament and burial paraphernalia, since some were found on the wrists of skeletons and some at the burial sites. The colour of bangles differs in shades, providing proof that their glassmaking technology was highly sophisticated. Glass bangles are believed to have been added to stone bangles in the Transition Period.

Glass beads & discs—Glass ornaments of the Prehistoric Era from around Pyawbwe and Halin: The collection consists of beads of different colour, shape and size including disc beads, a glass earring, and a glass bangle. The rest of the pieces are mostly beads in a variety of shapes such as claws, cylinders and cornerless cubes. Claws are one of the most common keepsake items, not only in Southeast Asia but also in India. Young boys wear them for strength and bravery.

Bead Culture

The bead culture is the most prominent and advanced aspect of the Bronze-Iron Transition Period. The fact that beads are found in abundance at all burial sites implies that beads were worn by most people of that time. The popularity of beads could be due to the fashion of those days, but most probably it would have been associated with their faiths and beliefs. Similar beads have also been found in Tibet, India, Mesopotamia, and Southeast Asian countries. Some even suggest that beads were used at that time as trade beads.

Bead Material

Bead materials are basically of two types: organic and inorganic. Organic materials comprise amber, fossilized wood, shell, coral, pearl, bone and ivory. Inorganic materials include gold, silver, bronze, metal, glass, clay, terracotta and semi-precious stone. Early beads were made of stone, talc, terracotta, shell and bone. Later, plain and etched semi-precious stone beads appeared on the scene. Materials include carnelian, agate, chalcedony, chrysophrase, talc, quartz, jadeite, jade, amethyst, aquamarine, and glass.

From numerous finished and quite a number of unfinished beads found at prehistoric sites of the Samon Valley, we can infer that those places were once major sites in the manufacture of ancient beads.

To date, raw materials like carnelian, chalcedony, chrysophrase, talc, quartz, amethyst, aquamarine, and agate can still be obtained in abundance from mineral mines in Bamaw, Mogok, Popa, Hba-ahn, Dawei (Tavoy) and many other sources in Myanmar.

Technology

The advanced technology of the Bronze-Iron Transition period is apparent in their unique drill-hole technology which involved drilling very tiny holes, sometimes as small as 0.05 mm in diameter, from opposing sides and making them meet in the middle. The people of the Samon Valley could drill incredibly long, fine, zigzag-shaped bores into beads of some length. This art seems to have been lost somewhere through the ages, and in this respect, today’s craftsmen cannot match their superb work without the help of sophisticated technology like laser beams.

Evolution of Bronze-Iron Bead Technology

Stage 1: In the very early part of Bronze-Iron bead history, only plain beads made an appearance. Craftsmen of the Bronze-Iron transition period were already well acquainted with the technology for the shaping of stones from previous ages. Polishing was done when the desired stone shapes were formed by filing and shaping. The quality of polishing by the Bronze-Iron people was so remarkable that their polished stones could maintain their lustre into modern times.

Stage 2: Although Bronze Age people had already started using beads of semi-precious stones in various shapes, it seems that etching technology was still unknown to them. They were able to etch designs on stone beads until the Transition Period. Following the plain beads, the bead surface was incised to make lines, dots, and circles on the beads of different shapes.

Stage 3: When the application of heat on stone became possible and commenced, powdered chemicals were used to fill the incisions and produce inlaid designs.

Stage 4: The technique of alkaline dyeing, bleaching and etching is one of the most outstanding achievements of the Bronze-Iron transition period. Possibly linked to the advancement of alchemy, heating techniques developed as powder-filled incision techniques diminished. Black or white chemical paste was applied to carnelian, agate, or fossilized wood prior to heating the stones.

With the application of heat to a certain temperature, the granule composition of the silica group stone becomes loose. The molten chemical seeps into the loose spaces and becomes a permanent colouring which would last for thousands of years. This technology of dyeing and etching developed greatly with the advancement of alchemy. Dyeing was carried out using seven (hot) chemicals in various mixtures such as arsenic, yellow orpiment, copper sulphate (blue vitriol), sulphur, cinnabar, ammonia and borax. They were used on agate, fossilized wood, or the silica group for the black on white effect. For the black on red effect, the chemicals were used on carnelian.

Bleaching and Etching made use of white on black or white on red designs only. White etching would appear on agate or carnelian. Four (cold) chemicals such as saltpetre (KNO3), natron (NaOH), quick lime (CaO) and salt (NaCl) were used. The basic concept behind dyeing and etching was most probably to represent contrast ideas concerning their faiths and beliefs such as ‘Yin and Yang’, ‘Sun and Moon’, ‘Hot and Cold’, ‘Male and Female’, and ‘Life and Death’. Contrast colours such as black & white, red & white, black & red, were used to represent all these concepts.

Stage 5: Carnelian and agate were heated for white etching and black dyeing to make more sophisticated beads known as tri-coloured leech Beads, an outstanding design, most commonly of black and white, on orange carnelian pieces.

This amendable and noteworthy technology of the Bronze-Iron Transition period is where bleaching, dyeing, and etching were used together. First, thick black strips were dyed on red carnelian stones. After that, etching of white lines was applied to the border of black and red so as to overlay the black border and make the design neat. These Tricoloured etched beads are regarded as masterpieces of the period.

Some scholars associate them with dZi beads, but their relationship to the Tibetan dZi beads, which are highly valued among collectors, is unclear. Tibetans revered their etched agate dZi beads as having supernatural origins. As another evidence of the remarkable work of the craftsmen, rare animal figurine beads with etched designs were also yielded from the Samon Valley sites.

From the use of these techniques, five different bead categories emerged. One popular assumption is that the ancient beads of Myanmar are products of these techniques, and are related to the etched beads of neighbouring countries. NB: Heating technology has served as the nerve centre for all developments and innovations throughout history. It could be said that it is one of the major catalysts for today’s industrial and electronic development.

Shape and Design

Beads may be categorized into two main types of shape and design: geometric and non-geometric.

Geometric shapes for the beads of that time are round, cylindrical, oblong, oval, tetrahedral, polyhedral, tabular, spherical, conical, bi-conical, crescent, rectangular, square, axe, disc, ring and collared beads, among many others.

Geometric designs on etched beads not only came into fashion, but also had symbolic values. Numerous line-decorated beads are found at the Prehistoric sites of the BronzeIron Transition Period in Myanmar.

The line-decorated design with simple stripes of white on beads is believed to have been very popular among the people of those days.

Quite a few eye design etched beads are also among the finds. These etched eye beads were used either as amulets or as decorative ornaments. The eyes supposedly represent the windows of the soul. Some believe that the eyes are the Gifts of God that protects people against evil. The eye beads of the Samon Valley may have had close association with the Tibetan dZi beads. The number of eyes on these Tibetan beads represents different meanings which contribute towards their significance.

Other noteworthy line designs such as zig-zag: (horizontal waves), zip (fish bone), cross, dots, squares, angles, triangles, rhombuses, webs, mesh-wire, stars and all sort of symmetrical designs can also be observed on beads of all shapes.

Non-geometric shapes

Non-geometric shapes include figurines, claws, flowers, twin lotuses, etc.

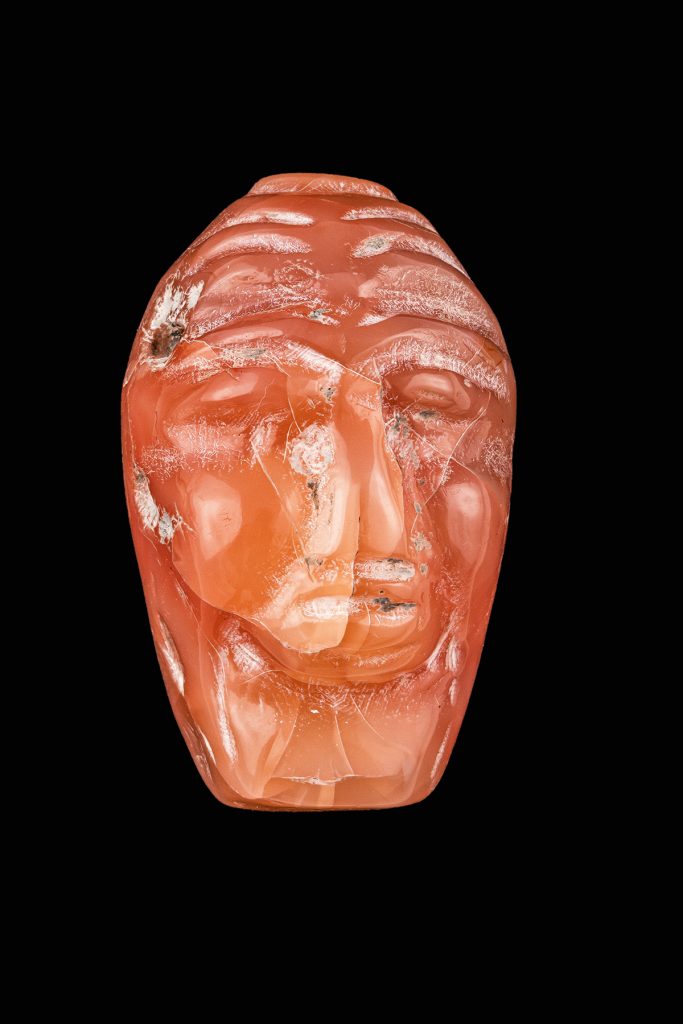

Figurines

Figurine beads play an important role in Myanmar culture because they portray the faiths, beliefs and symbolic values of the people more clearly than most other artefacts. It is believed that prehistoric inhabitants practiced animism, worshiped gods and goddesses of nature and also believed in totemic cults. They created figurines probably as charms, amulets and keepsakes. Semi-precious stones were most commonly used where they were made into the images of human beings and animals.

Rare figurines

Among the rare figurines, those in human form are believed to portray deities who may have been worshiped and prayed to for guidance, protection and wish fulfilment. Human figurines have been found in the Samon Valley only. Figurine beads play an important role in Myanmar culture because they portray the faiths, beliefs and symbolic values of the people… Arts of Southeast Asia / Art History Lion and fish figures have been found exclusively in the Samon Valley. It is the author’s opinion that the images of lions are drawn from western cultures and the fish draw from the influences of Asian cultures. This is based upon the fact that Samon Valley used to be at the crossroads of the eastern and western trade empires where traders met and exchange not only goods but also cultures, faiths, and concepts. Other rare figurines found from the prehistoric site include: dog, crocodile, goat, lizard, monkey, frog, bear, etc.

Common figurines

Most common are the figures of tigers, elephants, turtles and birds. The reasons for their popularity have not been determined, but it is thought to have been related to the values attributed to a particular creature, for example, tigers stand for bravery, elephants represent might, turtles longevity, and so on.

Tiger

Excavated tiger figurines from the Samon Valley are mostly made of carnelians which have a very close morphological relationship to the Qin Dynasty (221 – 207 BC) “Tally Tigers” of China. The belief and the use of tiger figurines may have derived from Western Zhou Dynasty (11th to 8th century BC). A tiger figurine made of marble from the Western Zhou Dynasty is displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of New York. Quite a number of tiger figurines have been unearthed from the ancient prehistoric sites in Myanmar. Among them is a tiger figurine with a cub in its mouth that stands out from the rest. This figurine is thought to be a reproduction or an adaptation of a bronze figurine of the West Zhou Dynasty of China. The bronze figurine has engraved line designs on the body. It is now on display at the Shaanxi Baoji Municipal Museum, Shaanxi Province in China. The difference between Samon and Chinese tiger figurines lies in the fact that Samon tigers were normally carved out of stone and the Chinese tigers are cast in bronze. In Samon, such figurines were used as beads due to the presence of bead holes, whereas no bead holes have been observed on Chinese tigers. Although there may be differences, the local carnelian tigers hint that the Samon Valley society already had trade connections with China, which continued into the Pyu Era and hence to this day.

Elephant

Probably an image from animism in the first place because Buddhism was still unknown to the Samon people at that time. Later on, from the exchange of culture with India and other countries, their original beliefs must have merged with Buddhism or Hinduism. So would their concept of the elephant, which also plays an important part in those religions. This new concepts seem to have flourished from the Pyu era along with their culture. The image of the elephant is still found in today’s society in Myanmar though the concept may have varied to a certain extent.

Turtles

The images could have been derived from Chinese beliefs representing longevity. No information has been obtained on how the ancient Chinese discovered the longevity of turtles but it turns out to be a scientific fact. According to Wikipedia, sea turtles reach their juvenility only at the age of 150 years and their life span covers way beyond 200 years.

Birds

Some of the images are assumed to be of the Chinese long tailed phoenix which represents auspiciousness. Although there are few citations, this ancient bird is thought to have appeared in China as early as the Neolithic period. The image of the phoenix is said to have been observed on jade and pottery motifs decorating bronze as well as bronze and jade figurines. The image was assumed by many to have been a good-luck totem for the Chinese. Regard for the bird could have been carried over to southern locations like the Samon Valley when the Chinese moved southward to flee from their country or to search for greener pastures. Images of other birds can also be observed. It seems that the craftsmen were inspired by birds in the natural environment. The figurines and their representations indicate that close relationship with China since the 11th Century BC and their involvement and influence on the local people are undeniable.

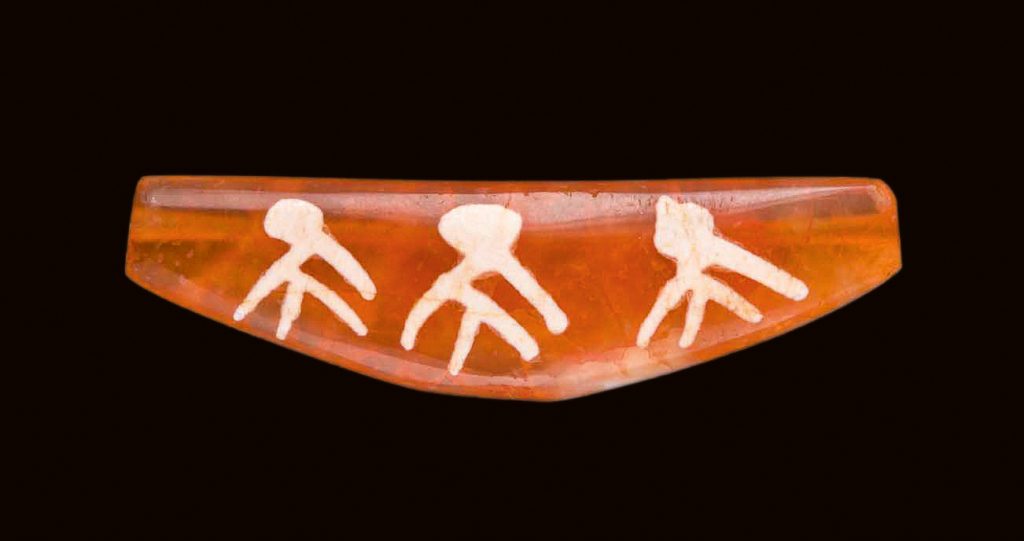

Non-geometric designs

Humans, animals, trees, stars, and early inscriptions like ‘ma’, which may represent mother goddess or fertility, are a few examples of non-geometric designs of this period. Letters etched on carnelian beads can still be observed from the Pyu Era and this phenomenon indicates that the technology was carried over from the prehistoric period and survived until the Pyu period.

Many kinds of burial customs have been observed at the sites of this period.

- Human: Most of the etchings of humans have strange features such as having three fingers and the head of a mythical creature. This could be an image of a deity.

- Deer: Etchings of deer make their most frequent appearance on carnelian beads. As mentioned in the introduction, local inhabitants rely heavily on deer to help them find salt mines. Therefore, it is still believed by the locals of today that deer bring luck and prosperity. It is also seen in the paintings of scenes from Buddhism. However there is one carnelian bead of a tiger with an image of a deer on it. It could be an implication that tigers are harmful towards deer.

- Tree: It is a well-accepted fact that humans have worshiped trees, the sun, the moon, or whatever they regarded as a power source before the advent of religion. It could also be an influence from the Tree of life concept from the west. Regardless of the source, it is apparent that those ancient people had a high regard for trees.

- Dog: Dogs are among the few animals that human beings could domesticate. Dogs are master-friendly, and this would be the characteristic that would give them a place in the lives of the pre-historic people.

Thus, prehistoric bead culture is crucial in terms of the study of culture, society, trade and beliefs throughout our history.

Glass bangles of the Prehistoric Era were used as ornament and burial paraphernalia, since some have been found on the wrists of skeletons and some at burial sites. The colour of bangles differs in shades, providing proof that their glassmaking technology was highly sophisticated. Glass bangles are believed to have been added to stone bangles in the Transition Period.

Glass ornaments of the Prehistoric Era from around Pyawbwe and Halin. The collection consists of beads of different colour, shape and size, including disc beads, a glass earring and a glass bangle. The rest of the pieces are mostly beads of different shapes such as claws, cylinders and cubes with rounded corners. Claws are one of the most common keepsake items not only in Southeast Asia but also in India as well. Young boys wear them for strength and bravery.

Comb shaped etched carnelian bead strung with cylindrical quartz beads and round carnelian beads. Pieces with the rare comb-shape design and white line etchings are hard to come by. The centrepiece as above is typical of the prehistoric beads of Myanmar. Various sizes of etched agate ‘eye’ beads strung with gold spacers and convex rectangular etched agate beads of the Prehistoric Era. From evidence of the significant number of eye beads found at the ancient prehistoric sites, the design is believed to have been very popular in those days.

A carnelian figurine of a tiger with its cub in mouth: The figurine was found at a prehistoric site: Ywa-Htin-Gon near Pyawbwe. A figurine of a tiger itself may be found occasionally, but one with a cub in its mouth is quite unique.

Etched carnelian and agate beads strung with gold spacers. Carnelian beads with white line etching were found at ancient prehistoric sites of Mesopotamia, India, and Southeast Asia as well. Some of the etched carnelian beads such as the three centrepieces are of rare design.

Convex rectangular etched agate beads with gold spacers. Beads of this kind were found at prehistoric sites, as well as at ancient Pyu sites of Myanmar. The zigzag: or jagged designs are still popular to this day and have almost become the traditional design of Myanmar. People in Myanmar, including the ethnic groups, still wear costumes with the design woven or embroidered on their clothing especially for auspicious or formal occasions.

In the later part of the transition period, iron replaced bronze for weapons and tools as it was found to be much harder. They were able to forge iron and other materials as well. When people came to use bronze weapons less, bronze ornaments came into fashion. Both men and women wore bronze ornaments such as rings, earpieces, bangles, waist-ornaments and anklets. Furthermore, they continued using bronze ladles, pots, plates, etc. Small bronze bells of various shapes have been found on skeletons, around the neck, arms, waist or ankles. There is a strong indication, therefore, of their use as ornaments. Bigger bronze bells were found among the burial accessories. In addition to ornaments of the Bronze Age, bronze reliefs, bronze mirrors, bronze images of human and animals, bronze tools and equipment for metalworking were also found. Bronze seals and seal rings with images of humans and various creatures, ivory sword handles, and ivory beads have also been discovered at the prehistoric sites.

As far as metalworking and jewellery is concerned, they appeared to have managed to learn how to separate and purify metals, and they were able to extract gold and silver from other metals. However, there are also indications of cases where they melted gold nuggets or raw gold and used it as it was. Thus, gold and silver ornaments such as beads and jewellery were found in addition to the bronze ornaments in this latter part of the Bronze-Iron transition period. They also seemed to have discovered techniques for mercury amalgam gilding. Examples of this art are seen in small round gilded terracotta beads and gilded disconnected bronze bangles from the Bronze-Iron Age sites.

Moreover, the ornamental use of gold has been illustrated by an upper jawbone with eight teeth (upper central and lateral incisors, canines, and the 1st pre-molars) drilled with a pattern of 102 small cavities filled with gold foil or on the front surface of teeth to insert decorative florets of gold.

The source of this use of gold may have prompted Chinese references to the ‘Gold Teeth Comforter ship’. Chinese accounts of the Nanchao kingdom also mention the custom of the lowland people of capping the teeth with precious metals or lacquer. To date, however, this particular find recovered south of Halin, is unique, since none as such has been found so far in Myanmar (gold teeth).

The most distinctive features of the Bronze-Iron Age are the tricoloured etched beads, etched animal figurines, gold-filled teeth, and the use of gold and silver and gilding technology. With technology in bronze, glass, bead-making and metalworking, the later part of the Bronze-Iron Age/Pre-Pyu period advanced from the culture of the Transition Period.

It was a period when pre-Buddhist beliefs were turning to a stronger belief in Buddhism. In terms of Samon culture, observing the material remnants, we can conclude that this culture had an inter-relationship with the Dian Culture from today’s China (Northern part of Myanmar). Local cultures influenced by cultures of the north and west synthesize into the distinct Pyu Culture of Southeast Asia. From there, the Pyu civilization emerged as the first dynasty era in Myanmar, giving birth to the first gold culture of Southeast Asia in the 1st millennium AD.