The International Magazine of Arts and Antiques of Southeast Asia

Volume 1, Issue 2, May-June 2020.

Contents

Index to Advertisers

Preview

Editorial

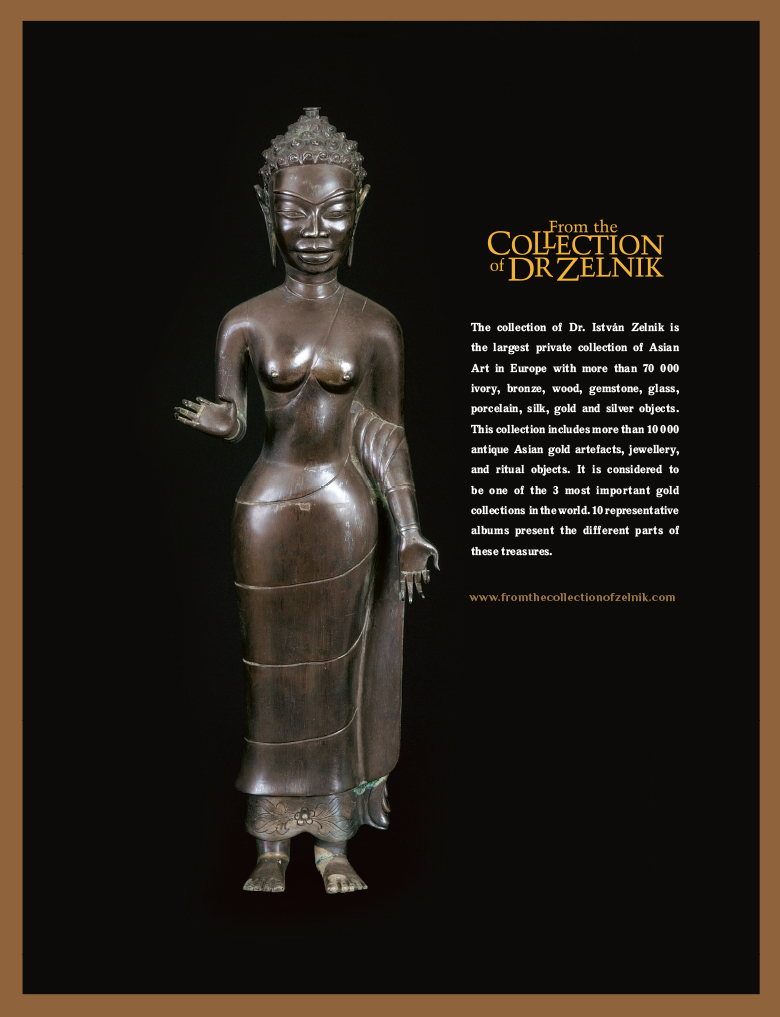

Ten years ago, my photographer friend Miklós Sulyok and I had the privilege of admiring, inspecting, handling and photographing this extraordinary collection in the museum vault, the first Europeans to do so. An album of Nguyen Dynasty imperial seals has been released, even so, sadly, they have not received the global recognition they deserve. We would like to make up for that shortcoming in this, the second issue of our magazine, which covers Vietnamese art and culture.

One little-known episode of the ‘adventurous’ story of these imperial seals is that during the August 1945 Revolution, at the fall of the empire, after the imperial seals had become the property of a new Vietnamese government led by Ho Chi Minh, they spent decades In the depths of Hanoi’s Western Lake Ho Tay, surviving first the French and then the American wartime bombing, and the attempts of adventurers to acquire them.

This second issue contains another sensation, namely the presentation of imperial hats, whose fate has been no less adventurous than that of the imperial seals. A rare manifestation of their “legend” and the patriotism connected to them is the unravelling of the story of this headgear. Accordingly, the imperial hats were sold by the national revolutionaries to a Haiphong merchant family in the late 1940s to buy weapons for the war against French colonists.

Legend has it that the family who bought the imperial hats—later “alien, tolerated, and re-educated”—retained them, concealing them for decades, until at the end of the Vietnam War they finally donated them to the state, disassembled and broken, with the silk parts damaged by the tropical climate. These imperial relics and their restoration are commemorated and presented by two outstanding Vietnamese historians.

As in the first issue, the second presents a special architectural monument, this time the one-pillar Pagoda ( Chua Mot Cot ), a really special Buddhist shrine, and this second issue of the magazine also gives an insight into Vietnamese archeology, the world of museums, and modern and contemporary Vietnamese art.

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoy this extraordinary cultural and artistic adventure through Indochina, Vietnam, and the mysterious lost world of the Cham kingdom

Dr. István Zelnik

Editor, President of the Editorial Board

The Preservation and Restoration of

Four Emperors’ Ceremonial Hats

Dr. Nguyen Dinh Chien and Dr. Nguyen Van Cuong

National Museum of Vietnamese History

On the afternoon of 30 August, 1944, at the Ngo Mon Gate of ‘Lau Ngu Phung’, Bao Dai, the last Emperor of the Nguyen Dynasty, declared to around 50 000 people in Hue, the capital of the kingdom, that he was abdicating. He handed over the royal seals and swords to a revolutionary government representative. On behalf of the new government, Tran Huy Lieu received these precious objects, and awarded a medal signifying ‘Citizen of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam’ to the former Emperor. After that, the royal seals and swords were moved to Hanoi for the meeting of the ‘Independence Day Declaration’ on 2 September, 1945.

Chua Mot Cot

The One Pillar Pagoda

Chua Mot Cot, the One Pillar Pagoda, is an historic Buddhist temple in Hanoi, the capital of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. The temple was built by Emperor Ly Thai Tong, who ruled from 1028 to 1054. According to court records, Ly Thai Tong was childless and dreamt that he met the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, who handed him a baby son while seated on a lotus flower. Ly Thai Tong then married a peasant girl that he had met and she bore him a son.

The emperor constructed the temple in gratitude for this in 1049 having been told by a monk named Thien Tue to build the temple by erecting a pillar in the middle of a lotus pond that resembled the one he had seen in his dream.

Kosa in the Religion and Art of Champa

by Dr. Ngo Van Doanh

The Mỹ Sơn stele inscriplion of Vikrāntavarman I, dated 609 śaka (687 A.D) records the donation of a kośa to Īśāneśvara, and a mukut . a [crown] to Bhadreśvara, by Prakāśadharma in 609 śaka (687 A.D): Having installed, out of devotion, a Kośa of Īśāneśvara (i.e. a Lin˙ ga of Śiva called Īśāneśvara) according to true rites, the illustrious Prakāśadharma gave a crown to Bhadreśvara. May this pair, Kośa and crown, like two pillars of his fame, exist unimpaired in this world, as long as the Sun and the Moon last… When the Sun rises, the Moon is gone; and when the Moon rises, the Sun sets – this is the rule of the Universe. But the spotless Moon which is the Kośa of Īśāneśvara, and the Sun which is the Crown of Bhadreśvara… May the revered king Vikrāntavarma triumph with his Moon-like silver Kośa, without eclipsing anybody else. (Majundar, 1985: 28) The Dong Dương Stele inscription of Indravarman II, dated 797 śaka (875 A.D) gives the same information about kośa.The Dong Son Ritual Gold Drum

by Peter Northover, Dr. Zsuzsanna Renner and Jean-François Hubert

Dong Son Culture

The Dong Son Culture is an important prehistoric Indo-Chinese culture. It was named after the village in northern Vietnam where many of its remains have been found. The Dong Son site shows that bronze culture was introduced into Indochina from the north (China), probably around 300 BC, the date of the earliest Dong Son remains. Dong Son was not solely a bronze culture; its people also used iron implements and Chinese cultural artifacts. Nevertheless, their bronze work, especially their production of bronze ritual drums, was of a high order.The Dong Son were seafaring people who apparently travelled and traded throughout Southeast Asia. They also cultivated rice and are credited with originating the process of changing the Red River delta area into a great rice-growing region. The Dong Son Culture, transformed by further Chinese and then Indian influence, became the basis of the general civilization of the region.

Editorial Board

Index of Advertisers – ARTS of SOUTHEAST ASIA: Art and Culture Vietnam, Volume 1, Issue 2

From the Collection of Dr. Zelnik, Switzerland

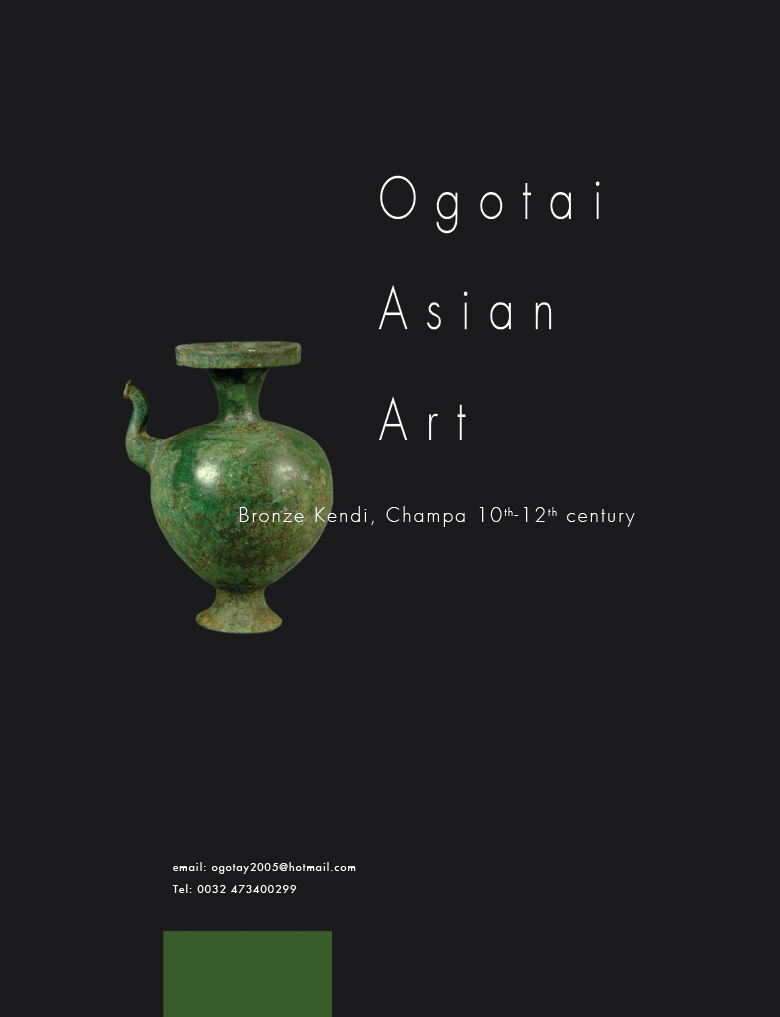

Ogotai Asian Art, Belgium

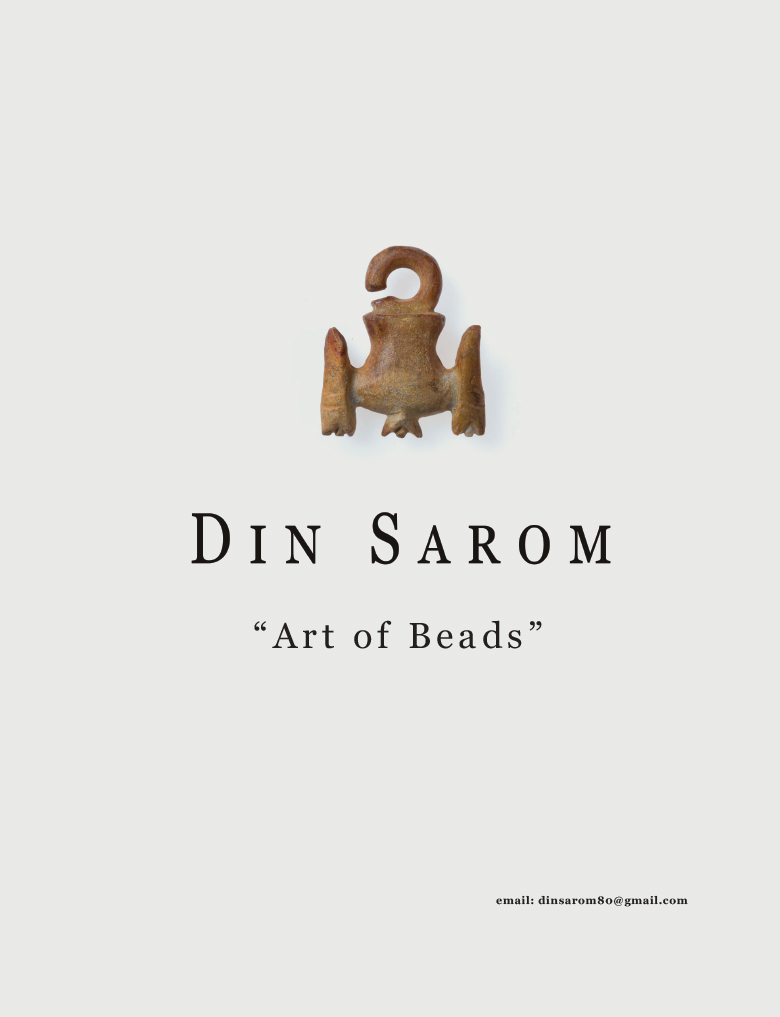

Din Sarom Asian Art Gallery, Belgium

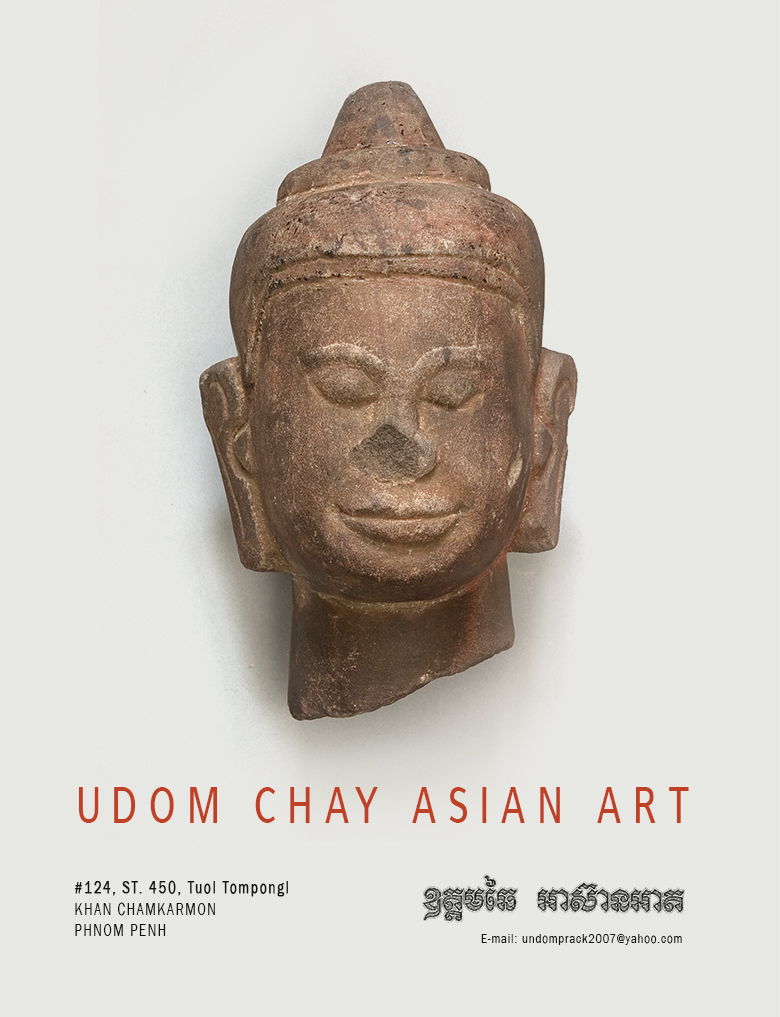

Udom Chay Asian Art, Cambodia

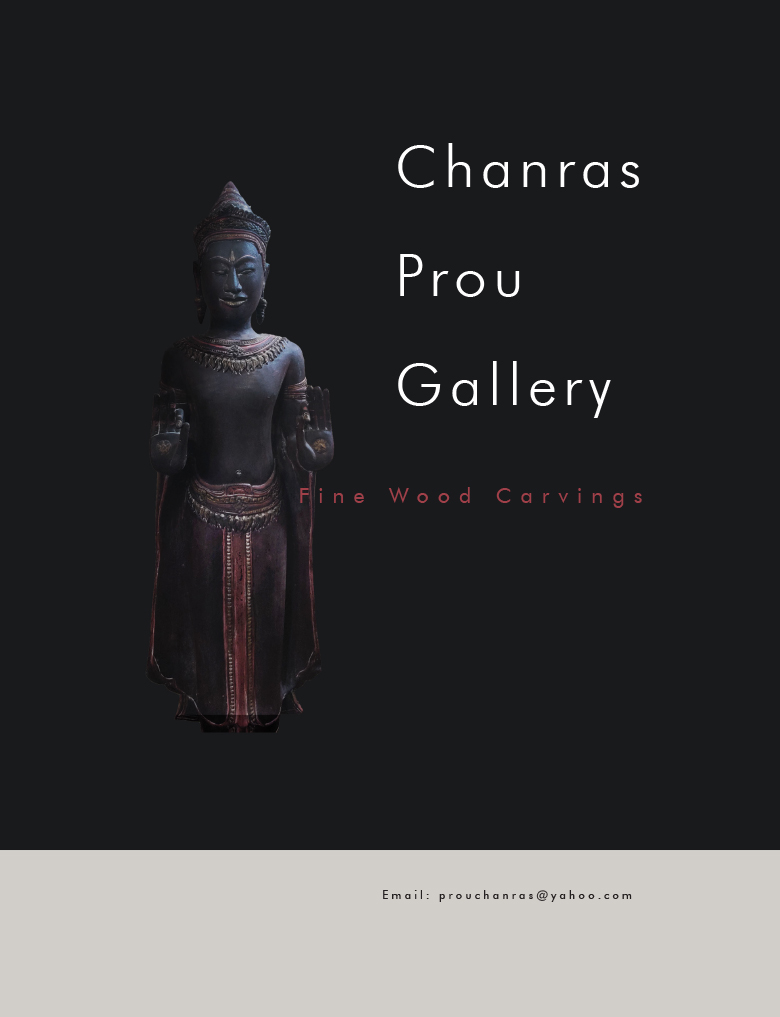

Chantas Prou Gallery, Cambodia

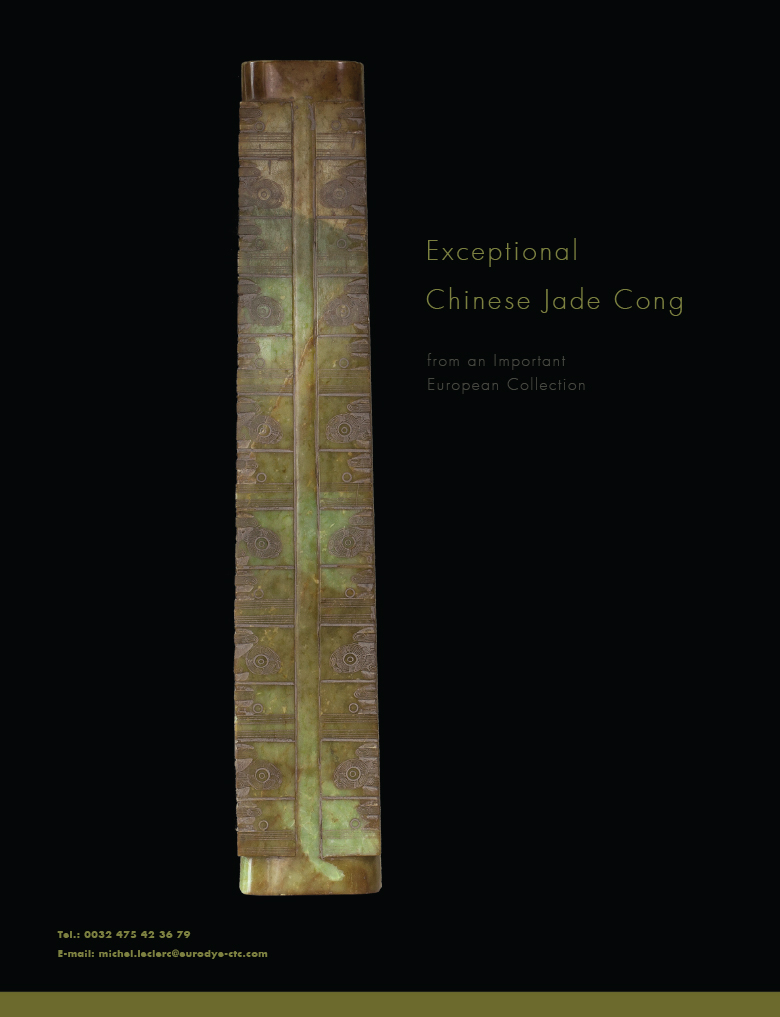

Michel Leclerc, Belgium

Lao Heng Heng, Cambodia

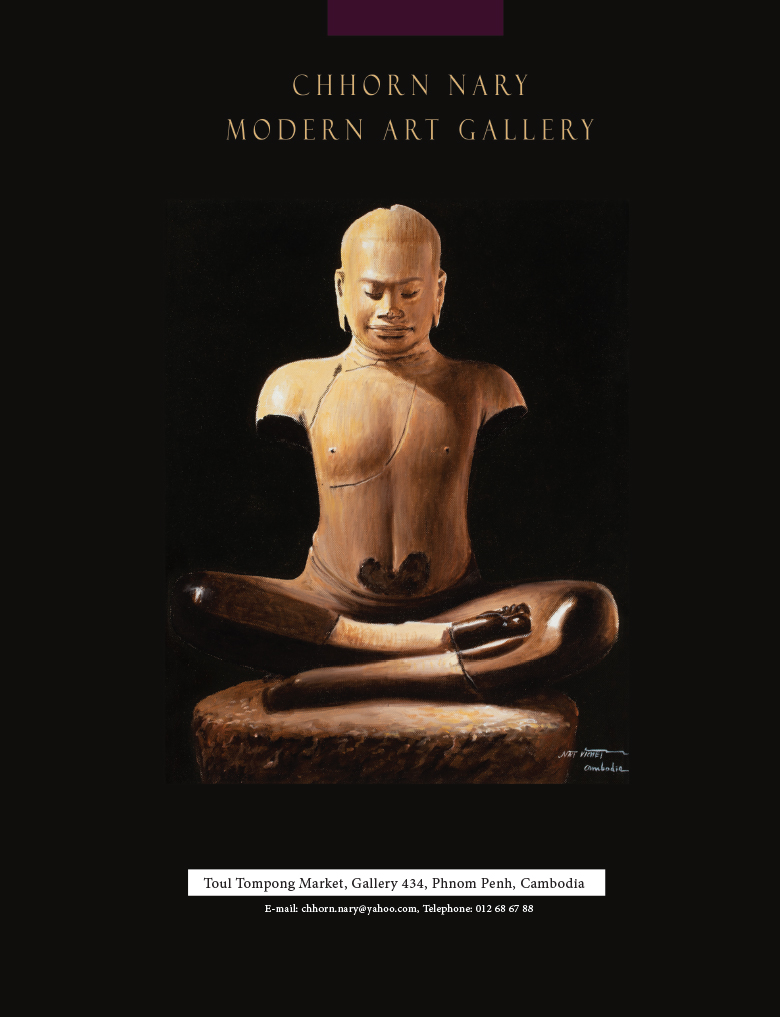

Chhorn Nary Modern Art Gallery, Cambodia

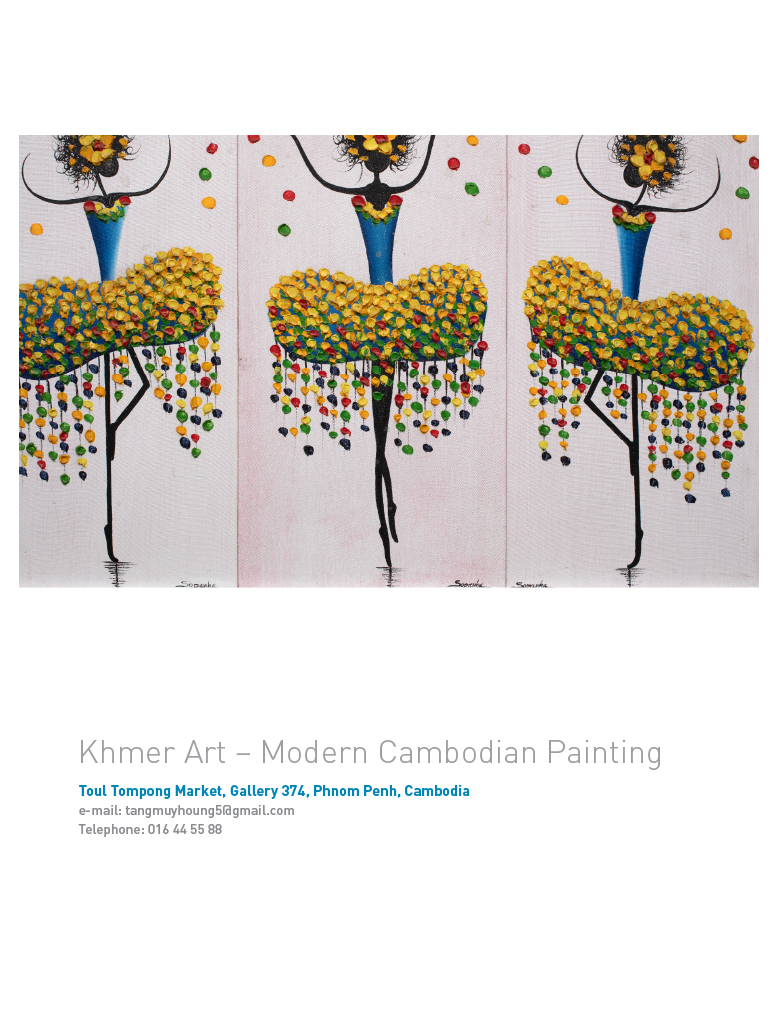

Khmer Art – Modern Cambodian Painting, Cambodia